Lawrence History Center

"Equal Pay for Equal Work"

Workin' 9 to 5

What a way to make a livin'

Barely gettin' by

It's all takin' and no givin'”

–Dolly Parton, “9 to 5”

Question: Are you paid as much as you’re worth?

Every person who has worked for pay has likely considered this question at some point – maybe when they pick up their paycheck or on the way home after a long day on the job.

For women, this question has an added weight. This weight comes from hundreds of years of undervaluing women’s labor. At the heart is a concept that continues to strike a chord with working women today: “Equal Pay for Equal Work.”

Equal Pay for Equal Work has been a rallying cry for women for decades. In what is known as the “gender wage gap,” US women are paid less than men. Nationally, women today are paid on average about 84 cents to $1 in men’s wages. The wage disparity is greater for many women of color and Indigenous women.

The concept of equal pay for equal work as we know it originated during the World Wars as women entered traditionally male-dominated positions. However, if we consider what equal pay for equal work means – being justly recognized and compensated for one’s labor – its origins in the United States can be traced to the colonial era.

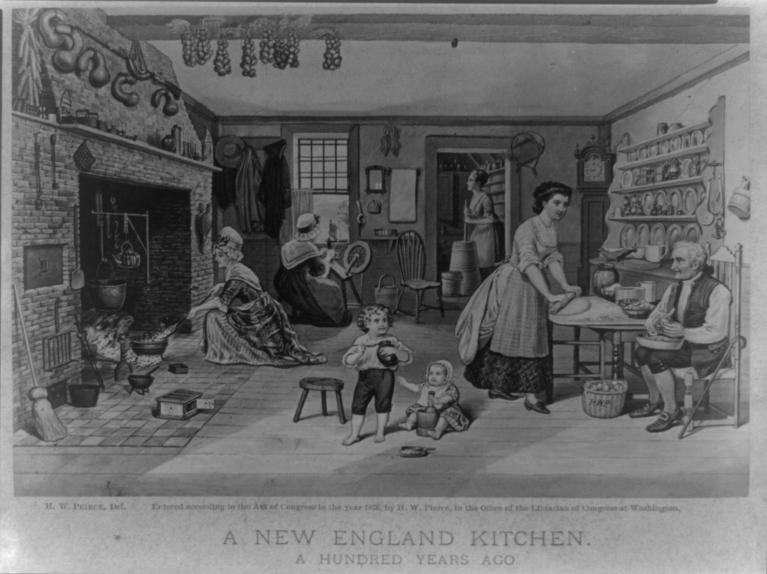

The Family Economy

In colonial New England, girls and women participated in the “family economy.” Women worked in the home or on the farm. While important, their work went mostly unpaid. If women did earn a wage for handiwork, the wage did not go to women, but rather to the head of the household – most often a man.

In this way, women’s work served to support men’s wage-earning labor. Women operated within a system that considered their work to be less valued and also underpaid–or not paid at all! It laid the foundation for women’s secondary economic status.

Question: Who takes on your family’s household work? How are they compensated?

The Worth of Women’s Work

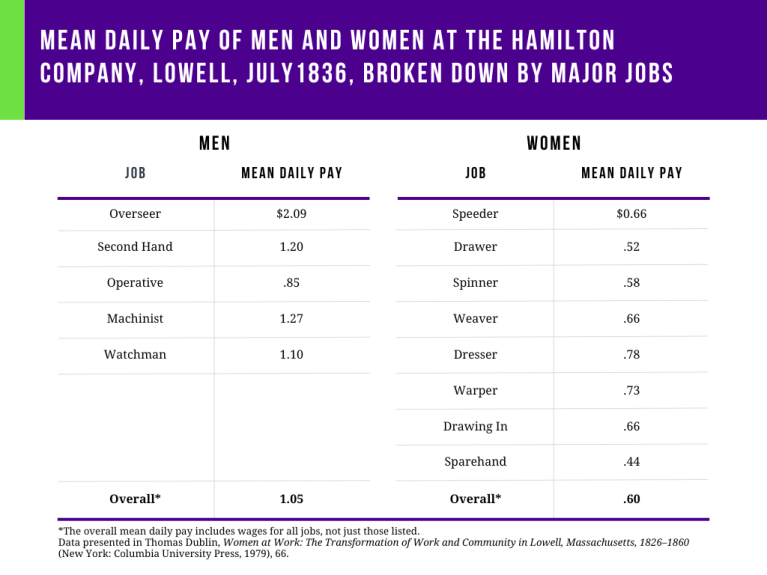

The family economy set the stage for gendered roles in labor – with men’s work being deemed of higher value than women’s. Men were considered the “real” wage-earners. If women worked for pay, their contributions were often seen as merely supplemental – not essential. And as the economy shifted in the industrial age of the late 1800s, this understanding of worth translated into compensation. Based on this belief that women’s jobs were secondary, early industries set lower value on the jobs women held, and paid them less for it.

As women continued to enter the workforce alongside men in the 20th century, societal norms continued to disrespect women’s labor. This disrespect of skill manifested into what we now call unequal pay.

Question: What does it mean to be justly compensated for your work?

As women joined the workforce, they quickly became aware that their work was undervalued, and therefore unjustly compensated. Women in Massachusetts in particular, began combating these notions regarding women’s worth and compensation in their labor. From the 1830s textile factories to the 1970s corporate offices, Massachusetts women throughout the centuries have organized and rallied for their worth and just compensation.

Why Massachusetts?

Women in the Commonwealth have often led the way in the fight for just compensation and equal pay in the United States. From the mill girls of the 1800s factories to today, Massachusetts working women have found their voices through collective action. They have petitioned, striked, organized, and won efforts to receive just wages for themselves and others.

The road has not always been easy. Working women have faced both victories and setbacks along the way. But each generation has continued the path towards just compensation for women’s labor and equal pay for equal work.

Massachusetts women know their worth…and they have shown it.

Mill Girls "Turn Out" in Lowell (1834-1836)

A Growing Worker Consciousness

The growth of factories in Massachusetts during the 1800s Industrial Revolution – the first in the country – resulted in a drastic change to the economy. Both employers and employees considered how women could participate in this burgeoning economy. Some employers hired girls and women to work in cotton or wool mills far from their family farms. Others hired women to work from their homes, most notably through shoemaking. Women earned wages independent from or complementary to the family economy, in some cases for the first time.

Question(s): Do you remember your first paying job? How much were you paid?

Initially awed by new wages and a role in the fast-paced industrial economy, women workers grew aware of their undervalued status. They knew their work was essential and they faced high demands, but their compensation was low. This growing self-awareness, or consciousness, often inspired action. Women learned that by organizing among themselves, they held collective power and could argue for better wages and greater respect.

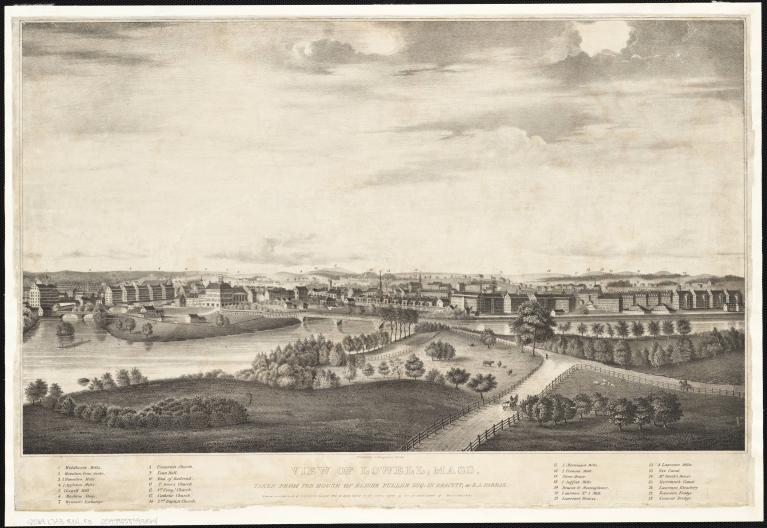

Lowell: A Mill Town

Winding its way down from New Hampshire, the Merrimack River curves along the northeast border of Massachusetts. For thousands of years, the Indigenous Pennacook Confederacy accessed the river before European colonization. European traders and settlers later used the river for transportation and trade.

The river’s strong current made it ideal for powering textile mills. In the 1800s, New England merchants built textile mills along the Merrimack’s banks. Soon towns emerged around the mills. Among the earliest and most prominent of these mill towns was Lowell, Massachusetts. With its first factory opening in 1823, Lowell became known as the center of the textile industry in New England.

Mill Girls and Factory Life

Employers recruited girls and young women to leave their farms and villages to join the factory workforce. “Mill girls,” as they were called, were women generally 15 to 30 years old. They worked six days a week and about 12 to 14 hours a day for almost 10 months of the year. They received monthly wages and stayed in boarding houses.

While some young women came to Lowell to support their families, others had different motivations. Some craved the economic independence that came with their own paycheck. Others found factory cities had more to offer than the small farms and towns where they grew up.

Question: Why did young women go to work in mill towns? Read the words of mill girls to find out.

I want you to consent to let me go to Lowell if you can. I think it would be much better for me than to stay about here. I could earn more to begin with than I can any where about here. I am in need of clothes which I cannot get if I stay about here and for that reason I want to go to Lowell or some other place.”

- Mary Stiles Paul (Montpelier, Vermont)

I have earned enough to school me awhile, & have not I a right to do so, or must I go home, like a dutiful girl, place the money in father’s hands, & then there goes all my hard earnings…I merely wish to go [to Oberlin College] because I think it the best way of spending the money I have worked so hard to earn…Others may find fault with me, and call me selfish, but I think I should spend my earnings as I please.”

- Lucy Ann (Clinton, Massachusetts)

There are girls here for every reason, and for no reason at all. I will speak to you of my acquaintances in the family here. One…is in the factory because she hates her mother-in-law…The one next her has a wealthy father, but…he wishes his daughters to maintain themselves. The next is here because there is no better place for her…The next has a 'well-off' mother, but she is a very pious woman, and will not buy her daughter so many pretty gowns and collars and ribbons...so she concluded to 'help herself.'…The next is here because her home is in a lonesome country village, and she cannot bear to remain where it is so dull. The next is here because her parents are poor, and she wishes to acquire the means to educate herself…”

- Harriet Farley

Although women had moved away from the traditional setting of the home or farm, their jobs in factories were still gender-specific. Men’s work included supervisory roles and jobs that required more training and technical skills. Women’s work focused on machine-tending, maintaining spinning and weaving machines. The separation of roles allowed employers to keep women’s wages significantly lower than men’s wages.

Regardless, many women who left their homes for this new life received wages for the first time. They found the work challenging but also dignified and rewarding. The economic independence that they gained in return for their work felt liberating.

Since I have wrote you, another pay day has come around. I earned 14 dollars and a half, nine and a half dollars beside my board... I like it well as ever and Sarah don’t I feel independent of everyone! The thought that I am living on no one is a happy one indeed to me.

Ann Sweet Appleton wrote to Sarah Appleton, January 8, 1847

Striking Against Wage Cuts

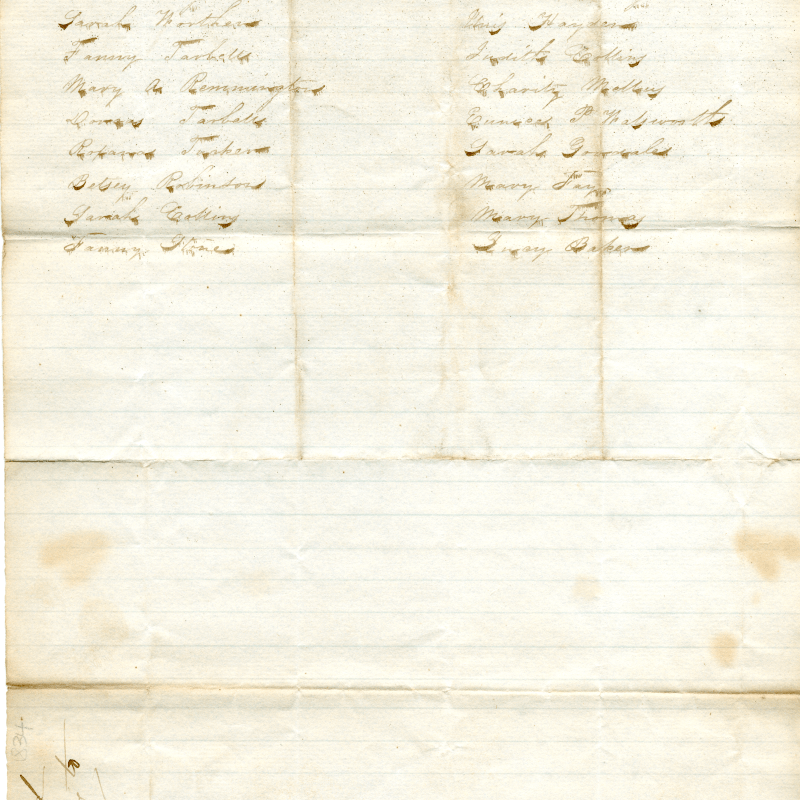

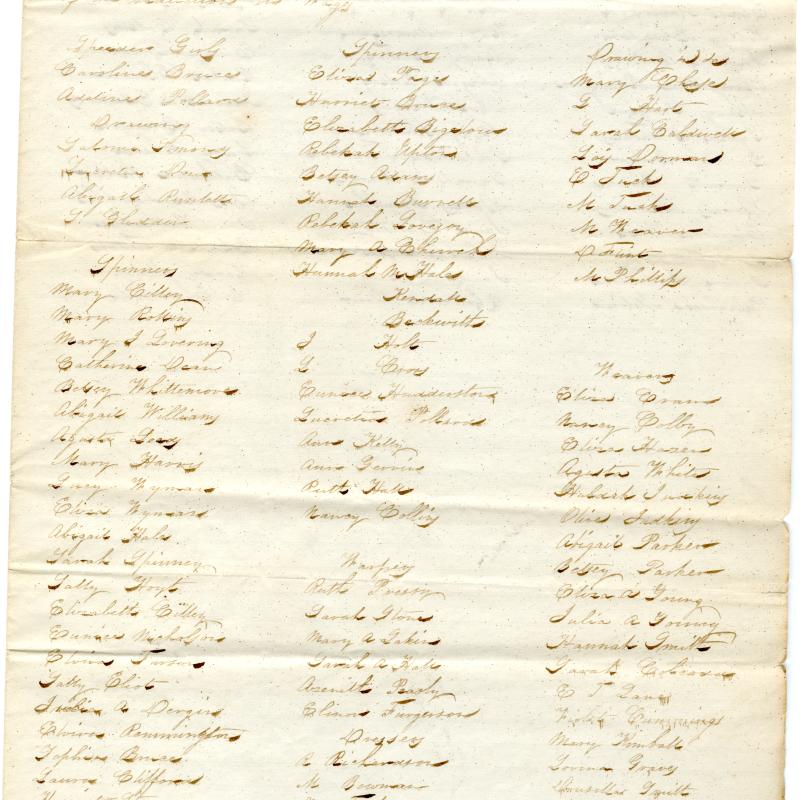

In the 1830s, Lowell mill girls faced two instances of wage cuts. Employers wanted to increase production demands and reduce labor costs. The pay decreases not only eroded the value of the workers’ labor, but they also threatened the workers’ economic independence. In 1834 and 1836, women workers responded to unjust wage cuts with “turn outs,” early forms of strikes.

In early 1834, mill owners planned to enact a 12.5% wage cut. As news of the proposed wage cut became more certain, unrest in the mills grew. Workers started petitioning against the wage cut and threatened to strike. A mill agent remarked:

A good deal of excitement exists in all the mills, not excepting ours, in relation to the proposed reduction. Papers are in circulation, & as I am informed, extensively signed, by which the females pledge themselves to leave if the reduction is made.”

Among the leaders of this petition was Julia Wilson. When mill agents fired Wilson for her involvement, over 800 women workers “turned out” to support her and to protest wage cuts.

The workers led a procession through town and held a mass outdoor rally. At this rally, they approved a set of resolutions demanding the restoration of pay for all workers.

Resolved, That we will not go back into the mill to work, unless our wages are continued to us as they have been.

Resolved, That none of us will go back unless they receive us all as one.

Resolved, That if any have not money enough to carry them home, they shall be supplied.

"Union is Power," Boston Post, February 19, 1834.

Despite the initial fervor, the turn out ended within a week. Mill owners, far more efficient and organized, removed the main leaders and forced workers to either return to work or go back to their homes in the countryside.

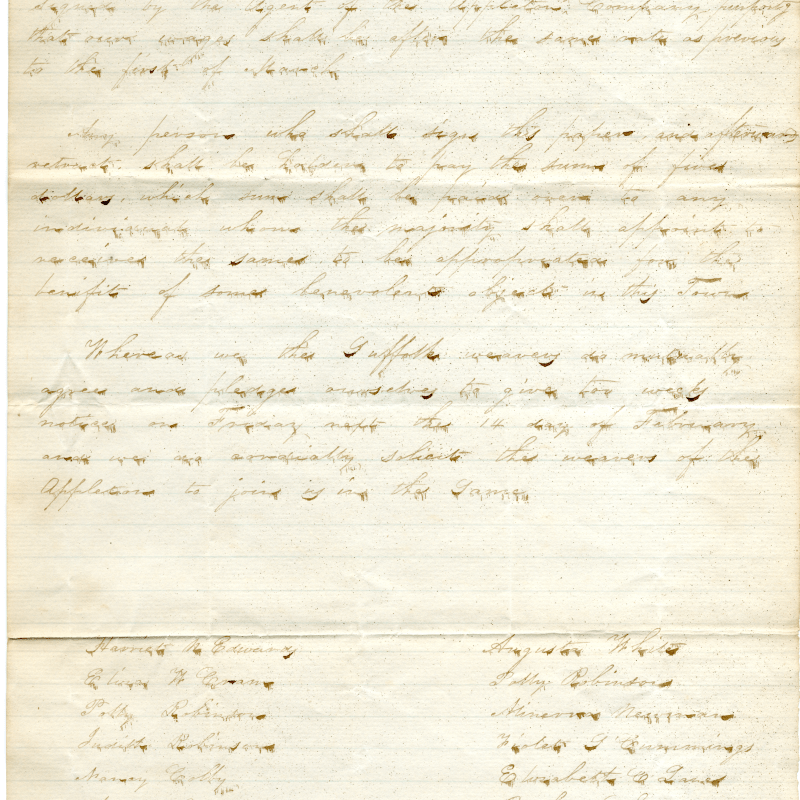

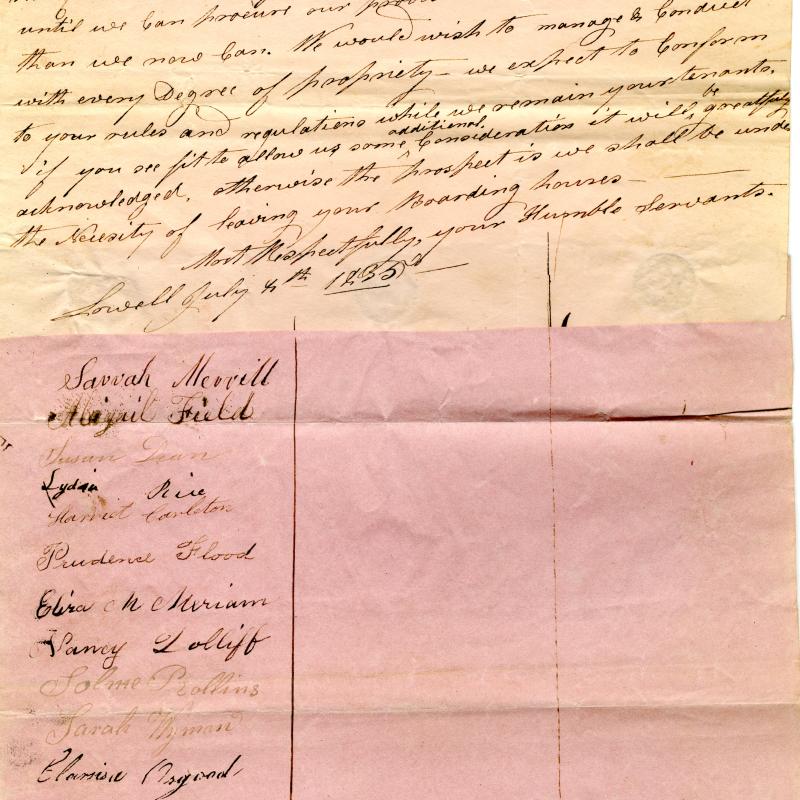

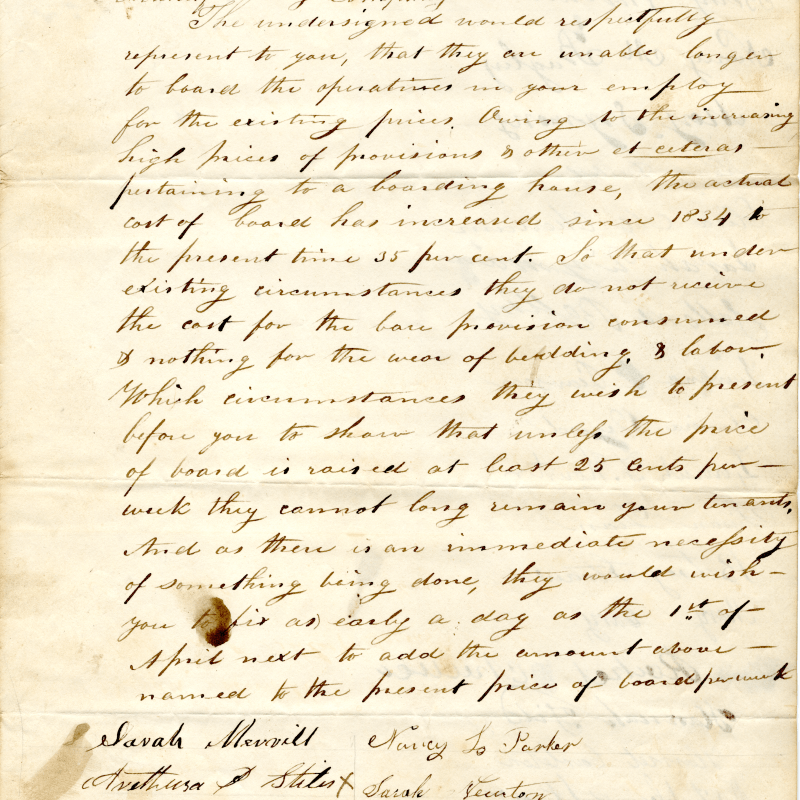

Two years later, the workers had learned their lessons and stood ready for another fight. At the request of boarding house matrons, mill owners approved an increase in room and board. However, the factories did not raise workers’ pay, which meant workers essentially faced a cut in take-home pay.

This time, the women workers better organized themselves for the turn out. Between 1,500 and 2,000 workers struck in 1836, which equalled 25-30% of the workforce. Strikers formed the Factory Girls’ Association to create structure and organization within the strike. The Association provided assistance to strikers, helping them cover room and board costs. Generally, strikers also had better timing with the economy; factories were in high production and needed workers to keep up with demand.

It was estimated that as many as twelve or fifteen hundred girls turned out, and walked in procession through the streets. They had neither flags nor music, but sang songs.

Harriet Hanson Robinson

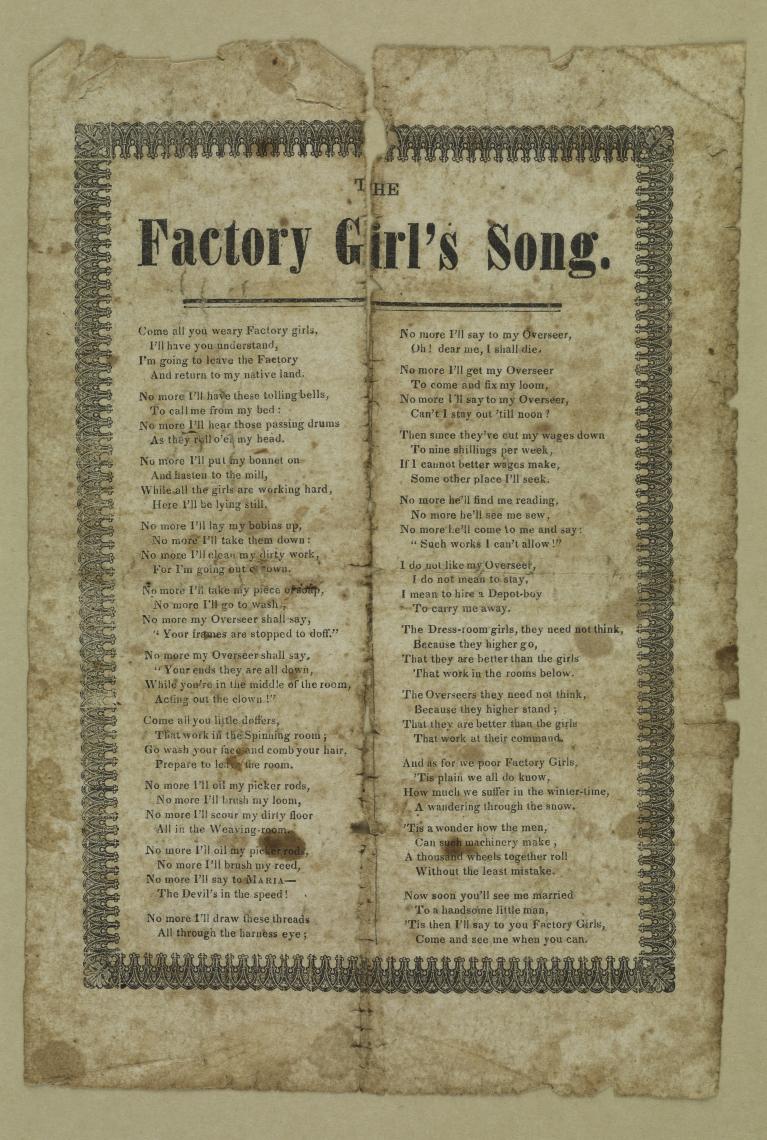

Folk songs have long been a part of the labor movement. “The Factory Girl’s Song” dates to the 1830s, with some historians linking its origins to Lowell. Read the stanzas and consider the day-to-day experiences of a mill girl. Read transcript. (Division of Home and Community Life, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

"I Cannot Be a Slave" in "Mill Girls"

During public gatherings and marches, women strikers sang songs and hymns. The protest song “I Cannot Be a Slave” originated at the time. Its melody derived from a well-known drinking song, “I Cannot Be a Nun.” Watch this rendition of “I Cannot Be a Slave” from the Saint Michael’s College 2020/2021 production “Mill Girls.” This traditional rendition was arranged by Tom Cleary.

Workers Achieve Success

After a few months, most companies agreed to the demands of the strikers. Some companies rescinded room and board increases for certain paid positions, while Merrimack and Boott Mills ended the room and board increases for all workers.

Profile: Harriet Hanson Robinson

Coming to Lowell at a young age, Harriet Hanson Robinson grew up in mill life. Her widowed mother operated a boarding house, and Harriet started working in the mills at a young age to help with family expenses. At just 10 years old, she worked as a “bobbin girl” in spinning rooms. Interested in writing, Robinson contributed to the Lowell workers’ magazine The Lowell Offering while working in the mills. She later became a proficient writer and poet, as well as an active suffragist. In her memoir, Loom and Spindle; or, Life among the Early Mill Girls (1898), Robinson remembers participating in the 1836 turnout as a young girl:

“I worked in a lower room, where I had heard the proposed strike fully, if not vehemently, discussed; I had been an ardent listener to what was said against this attempt at ‘oppression’ on the part of the corporation, and naturally I took sides with the strikers. When the day came on which the girls were to turn out, those in the upper rooms started first, and so many of them left that our mill was at once shut down. Then, when the girls in my room stood irresolute, uncertain what to do…and not one of them having the courage to lead off, I, who began to think they would not go out, after all their talk, became impatient, and started on ahead, saying, with childish bravado, ‘I don’t care what you do, I am going to turn out, whether any one else does or not;’ and I marched out, and was followed by the others.”

Over the course of the 1834 and 1836 turnouts, mill workers in Lowell became more aware of the value of using collective power to strike down unjust wage practices and safe-guard their economic independence and dignity as workers. They used a variety of different methods – petitioning, demonstrating, and striking – to ensure their voices would be heard and taken seriously.

"Give us a Fair Compensation": Women in the 1860 Lynn Shoeworkers’ Strike

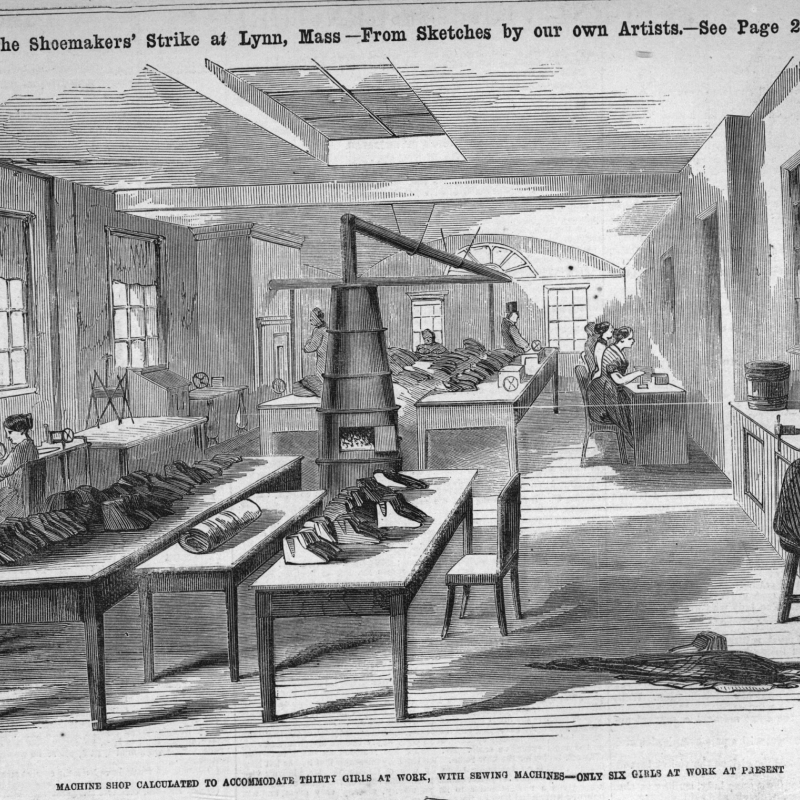

Homework and Factory Work in Shoemaking

While Lowell served as the center for the textile industry, Lynn and Essex County served as the center for the shoe industry. By the late 1700s, Lynn shoemakers had established themselves as specialists for women’s shoes.

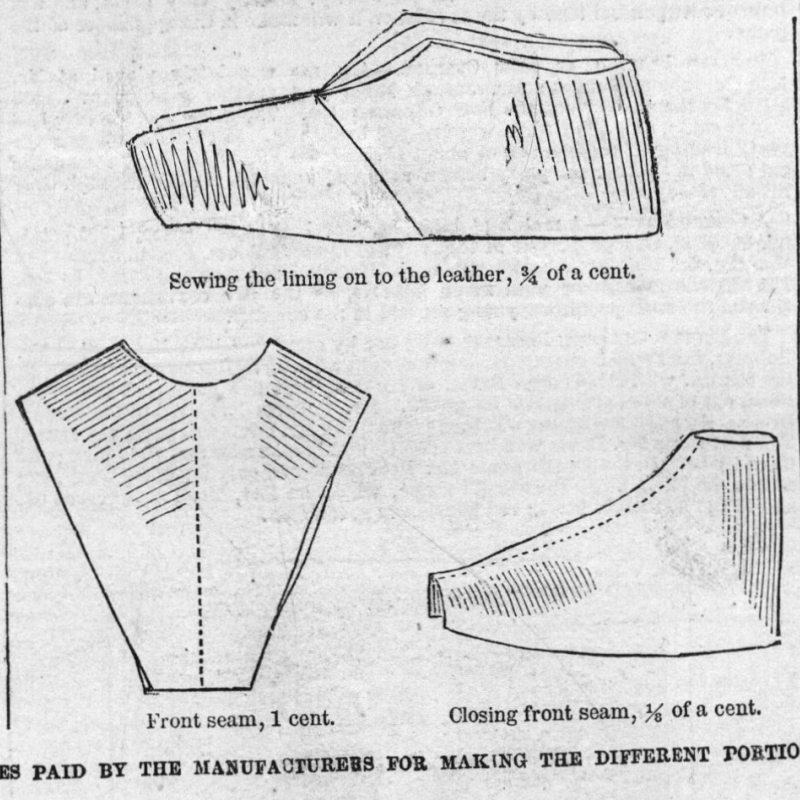

Much like textile work, labor in the shoe industry was divided based on gender. One of women’s primary roles involved binding or hand-sewing the leather upper parts of shoes. Because women could sew uppers within their homes alongside their domestic duties, many viewed this as an acceptable role for women. However, women either received low wages for their work or no independent wages – meaning women’s compensation was included in the compensation men received for their work. This was known as the “family wage” within the traditional family economy.

The growth of shoe production in the mid-1800s meant new opportunities for girls and young women. Young women from New England migrated to Lynn and other shoemaking towns for these new factory jobs in shoemaking. Some Lynn women continued to perform their work within the home to sew the upper parts of shoes, thanks to the invention of home sewing machines.

Regardless of whether women worked for companies in factories or at home, their labor in the shoe industry remained undervalued. As time passed, tensions arose between women homeworkers and factory workers. They differed in how they viewed themselves, their work, and the ways in which they were compensated. Traditional systems clashed with growing worker consciousness. No more clearly do we see this tension than in the 1860 shoemakers strike.

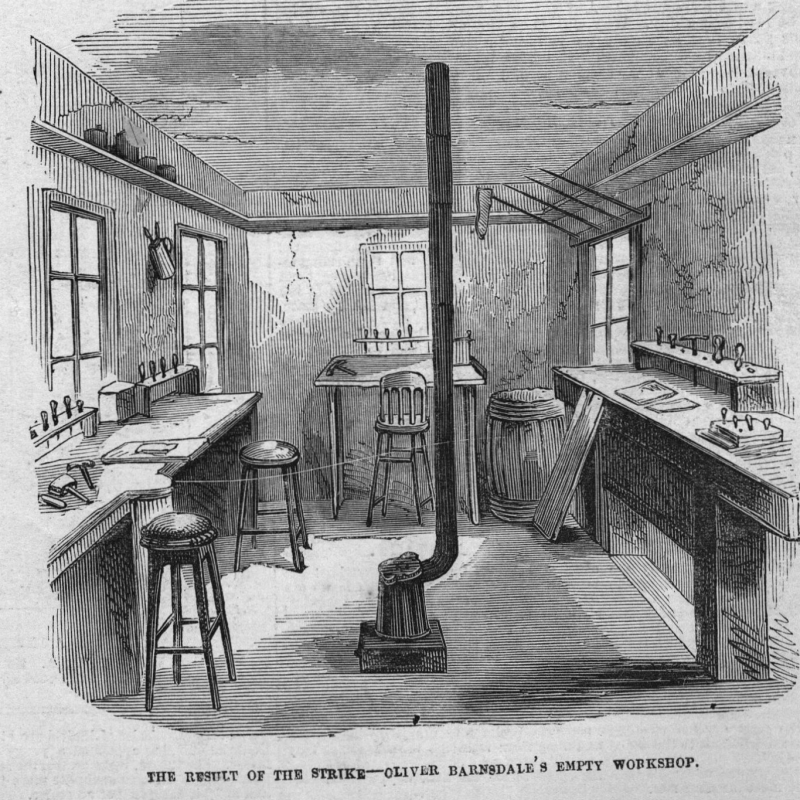

“Give us a Fair Compensation and We Will Labour Cheerfully”

When men shoemakers decided to strike in February 1860, the leaders invited women to strike in support of increasing men’s wages. They believed women’s presence in the strike would show how low wages for men negatively affected the traditional family.

To the male strike leaders’ surprise, women workers joined the strike not in support of wage increases for men, but for their own wage increases! During a women’s strike meeting on February 23, women factory workers such as Clara Brown led the call for women homeworkers and women factory workers to unite. Their cause? Better pay for women in the shoemaking industry.

Quickly organizing and drawing up a list of higher wage demands, both women homeworkers and factory workers voted in support of the measures on February 27. Although working in different realms – the factory and the home – all women workers recognized they deserved better compensation for their labor.

In following meetings, male strike leaders tried to rein in women’s demands. These men asked the women to align with the traditional idea that supporting men meant supporting the whole family. This led to conflict between women homeworkers and women factory workers. These factory workers, echoing the worker consciousness of Lowell mill girls, called on all women to advocate on behalf of their gender. Homeworkers argued to shift their alliance to the men of Lynn rather than the few vocal women factory workers who were seen as outsiders.

Question(s): Read the quotes that highlight the opposing viewpoints of the women strikers. Whose point of view do you agree with?

“Girls of Lynn, Girls of Lynn, do you hear that and will you stand it? Never, Never, Never. Strike then–strike at once; Demand 8 ½ cents for your work when the binding isn’t closed, and you’ll get it….keep still; don’t work your machines; let ‘em lie still till we get all we ask.”

- Clara Brown (pro-women's wages)

[Mary Damon explained] She was the wife of a poor man who for nine years had worked hard and industriously to obtain a bare subsistence. She wanted to cheer his heart, to hold up his hand, to prove to him that her interest and his were identical, and that she honored him for his spunk. Therefore it was with all her soul and body she was in for the strike, procession and all.”

-Mary Damon, via New York Times (pro-family wage)

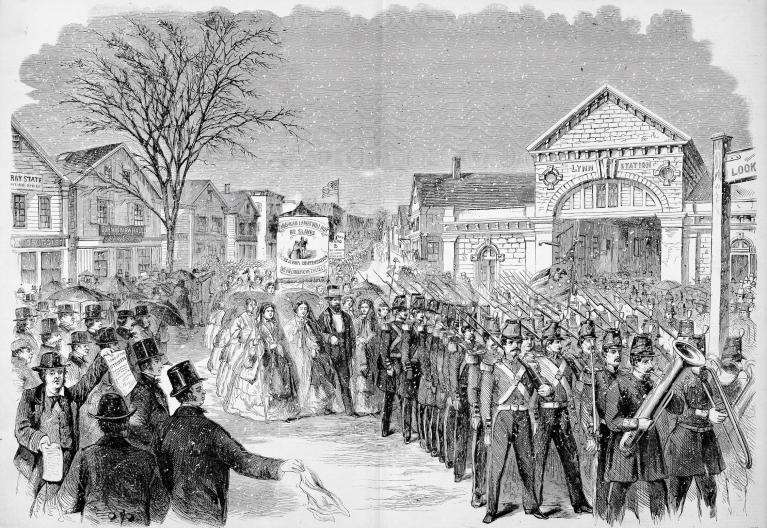

During a meeting on March 2, the will of the homeworkers won out and the previous vote for the higher wage demands for women was reversed. While many women factory workers abandoned the strike, about 800 homeworkers joined the male strikers in a procession a few days later.

"The Shoemakers' Strike in Lynn - Procession." Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, March 17, 1860

Overall, the strike largely ended in failure for both men and women strikers. Few employers met the demands for higher wages. In addition to highlighting the challenges workers – both men and women – faced in fighting for higher wages, it also showed the enduring strength of traditional expectations of women’s role in the workforce. The predominant practice, and highly supported view, of paying women within the context of the “family wage” rather than independently remained the norm.

The Lawrence Bread and Roses Strike (1912)

Women: A Unionizing Force

The turn of the 20th century brought a new era filled with activism and organizing to address social and economic injustices. One type of organizing was through labor unions. Labor unions had begun forming in response to the Industrial Revolution of the late 1800s. They grew in both support and power in the early 1900s.

Unions supported working people in fighting poor labor conditions, exploitation, and unjust compensation. They gave workers a way to structure their collective action to create change.

Question: In what ways do you see workers organize for better rights today?

In Massachusetts, women workers in the early 1900s continued to network and organize to improve conditions and receive just compensation. Not always union members themselves, they operated both within and beyond the formal union structure in order to advocate for wage increases to more accurately reflect the value of their work. In the early 1900s, two flashpoints – led by organized women – changed how women were compensated and seen in the labor movement.

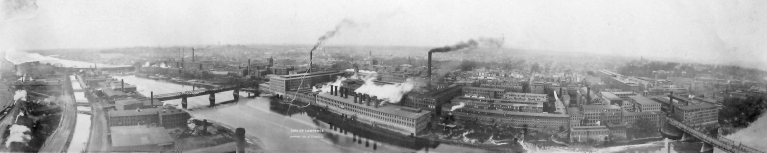

Lawrence and the Textile Industry

By the early 1900s, Lawrence, Massachusetts had become a bustling textile city. Established after Lowell, Lawrence quickly grew to be one of the biggest producers of wool cloth in the world.

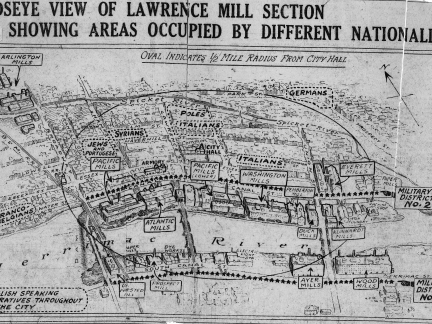

A panoramic view of Lawrence. (Lawrence History Center)

Lawrence as an Immigrant City

The booming textile industry had brought in a wave of immigrants to Lawrence. Some areas of the city became havens for different ethnic groups who established their own neighborhoods, while others included a diverse mix of ethnicities. In all, there were about 15 different ethnic groups (about 20-25 different nationalities) speaking more than 40 different languages. Women stood at the center of this immigrant city, building networks and communities.

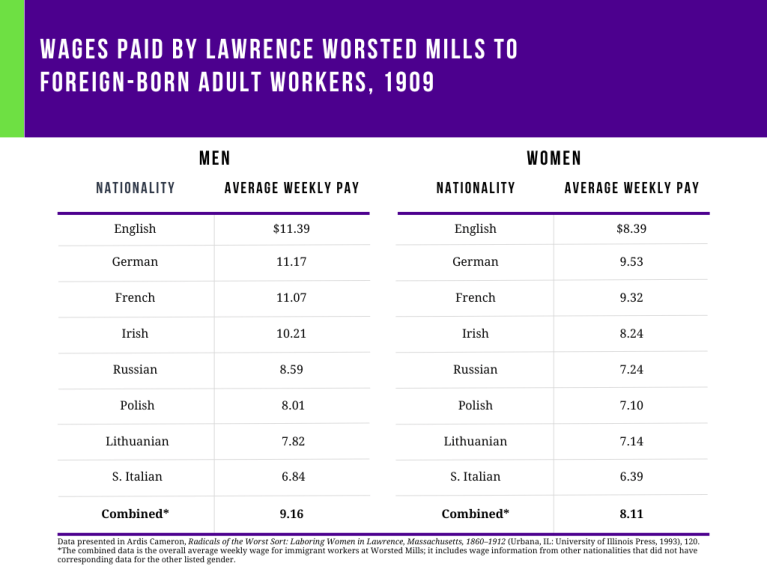

Lawrence History Center

Despite the wealth of the Lawrence textile industry, women workers continued to receive poor wages for their labor in mills. They were skilled, efficient, highly-productive with excellent quality results, yet their incomes were lower than male workers. And as immigrant women joined the workforce, they faced greater wage disparities. Women across ethnicities recognized this unjust treatment when it came to compensation for their work.

In Lawrence, mill owners and city leaders might not have expected that a working community so large and diverse would be able to organize. While unions had been building a presence in town, many workers had not yet officially joined a union. However, women across ethnicities had already been organizing. As historian Ardis Cameron suggests:

On street corners and stoops, in kitchens and markets, at bath houses and public laundries, on walks to and from factories, laboring women shared experiences, offered aid, nursed kin and neighbors, made friends and built alliances.”

These informal, women-built community networks laid the foundation for what would be one of the most influential strikes in the country’s history. All it needed was a spark.

“Better to starve fighting than to starve working!”

In 1911, Massachusetts passed a new law that reduced and limited weekly hours from 56 to 54 hours per week. With the law taking effect in 1912, Lawrence workers expressed concern that this law forcing them to work fewer hours would result in a wage reduction to match. Workers could not afford such a reduction.

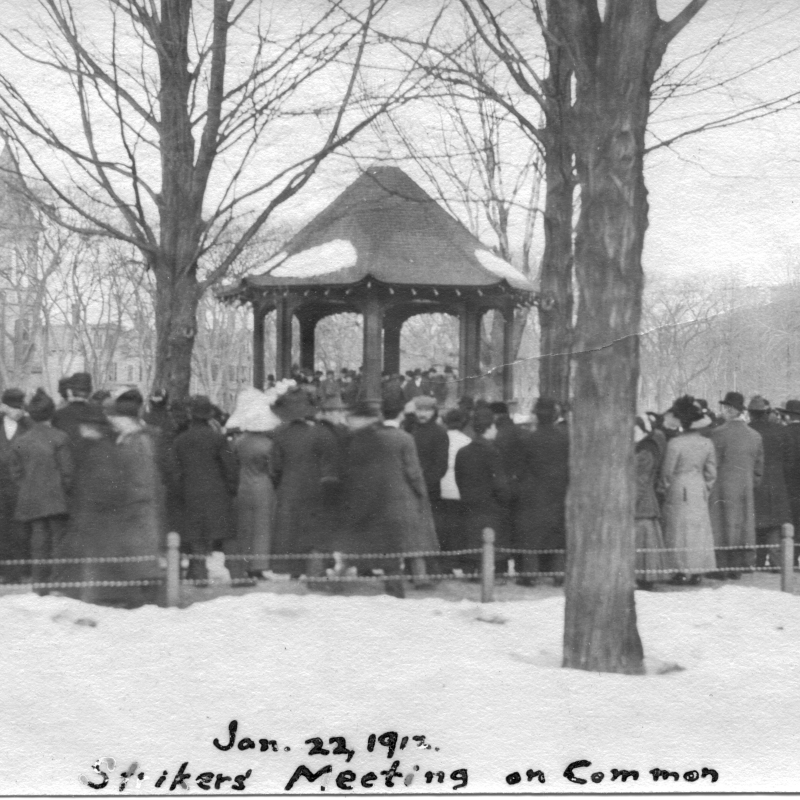

On January 11, 1912, the day they received their first paycheck of the year, workers learned their concerns were true. The first to react to the news were Polish women weavers at Everett Cotton Mills. They walked out of their workrooms shouting “Short pay, short pay!” As they marched through the streets of Lawrence the following day, other mill workers joined them.

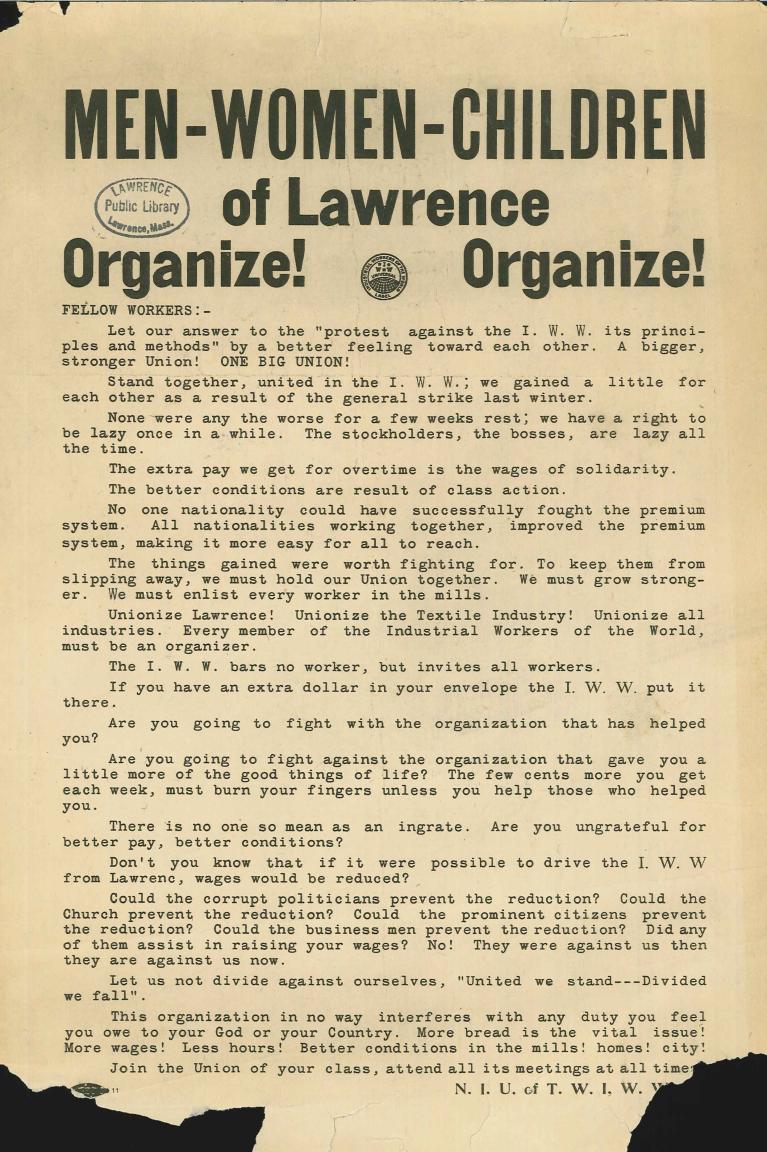

Within a week, 25,000 workers were on strike. Local chapters of the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) helped organize a strike committee. Soon IWW’s national leaders, including Joseph Ettor, Bill Haywood, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, came to Lawrence to provide support and assistance.

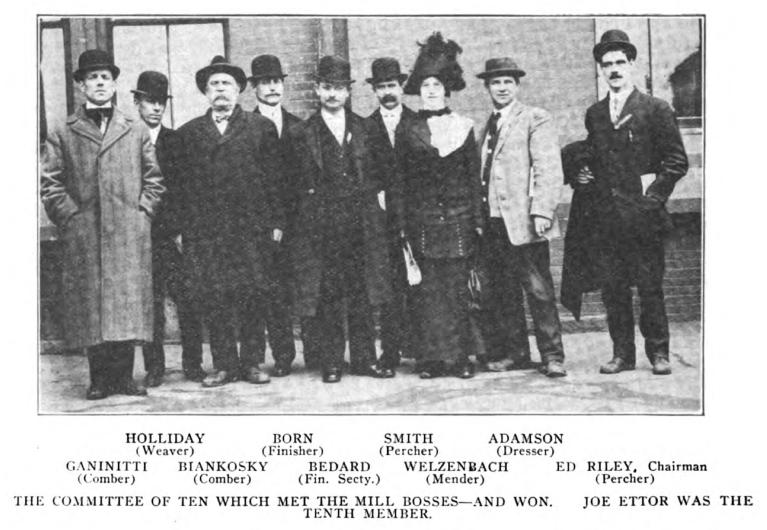

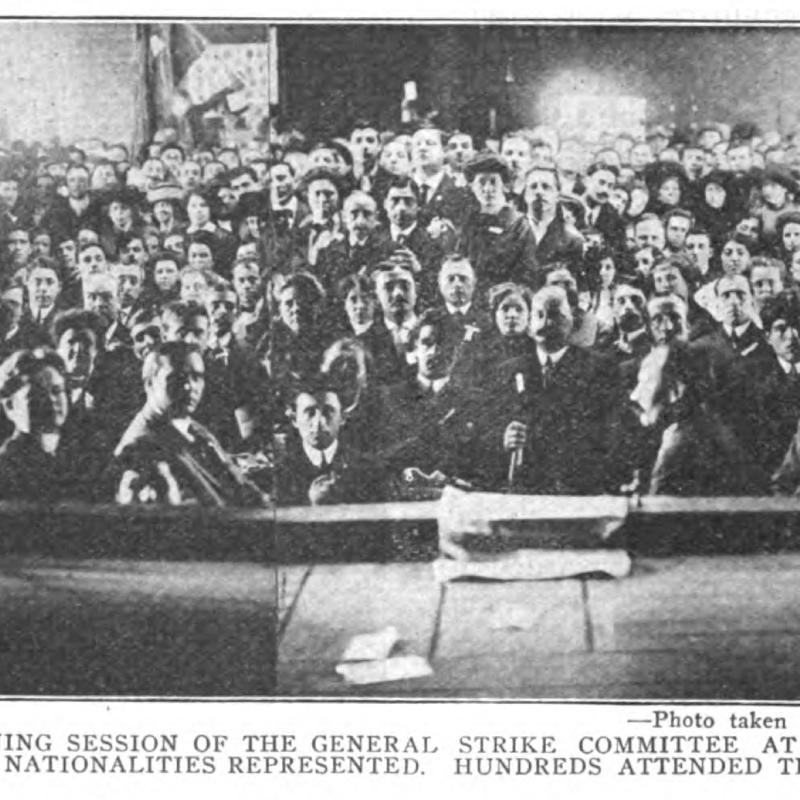

The executive strike committee, known as the Committee of 10, including one woman, negotiated with mill owners. A larger 50-person strike committee formed the general leadership group. This general strike committee included both men and women and embraced the diversity of the strikers. Members could speak multiple languages and represented most of the immigrant ethnicities present in Lawrence. The proceedings of strike meetings and fliers were translated into over 25 languages.

The women wanted to picket. They were strikers as well as wives and were valiant fighters.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, IWW Labor Leader

International Socialist Review vol. 10, no. 12 (April 1912)

Profile: Mrs. Annie Welzenbach

Annie Welzenbach, the lone woman on the Committee of 10 and just 24 years old, was a force to be reckoned with. Born in Canada to Polish immigrants, Welzenbach began working in mills when she was 14. She became highly regarded as a talented mender and among the highest paid women mill workers in the town. Despite her success, Welzenbach supported the strike. Able to speak English, German, Polish, and Yiddish, Welzenbach often spoke at strike meetings and rallies. She also successfully persuaded many workers to join the strike. These qualities made her an ideal candidate for the Committee of 10. Welzenbach’s power lay in her leadership both behind and in front of the scenes. Committed to her slogan of “Get out on the picket line,” Welzenbach often led strikers in marches and pickets.

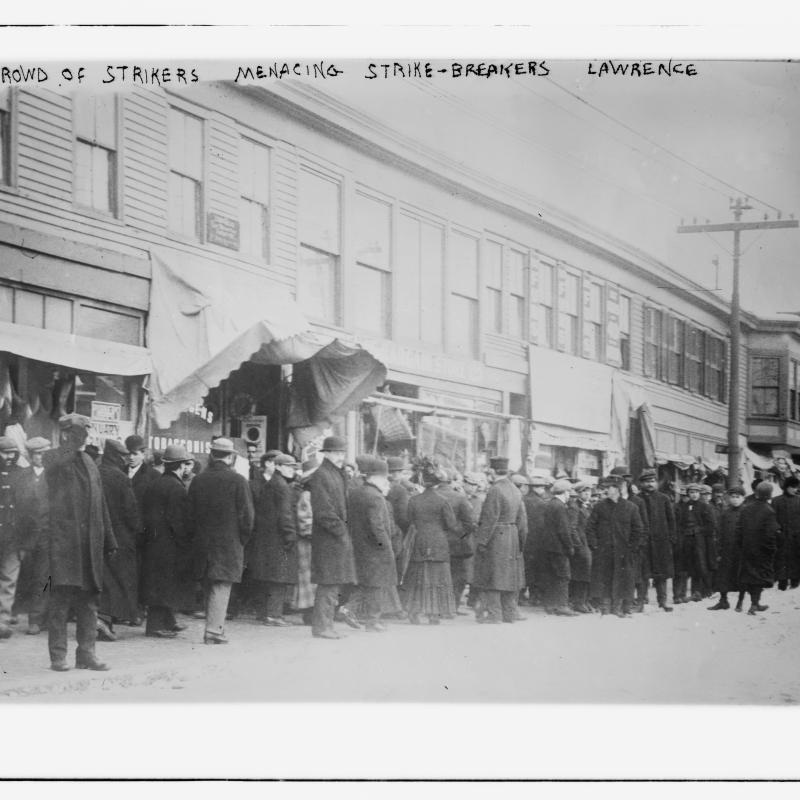

Within the union-led strike structure, women worked alongside men throughout the nine weeks of the strike. They served on the strike committee, marched and picketed, and attacked those who broke picket lines. Women were arrested, jailed, and one – Anna LoPizzo – tragically died during a clash with members of the militia.

Milne Special Collections & Archives Division, Dimond Library, University of New Hampshire, Durham, N.H.

We are not egged on by anyone or forced to go upon a picket line. We go there because we feel that it is but duty.

Female striker

Profile: Josephine Liss

Born in Kyiv and ethnically Polish, Josephine Liss represented the Polish community as a member of the strike committee. In addition to taking a formal leadership role, Liss served as a spy for the strikers. Taking the position of translator for the police, Liss positioned herself in a way that allowed her to help bail out numerous strikers and provide information to the strike committee. Liss also had run-ins with the police and militia herself, at one point being arrested for assaulting a soldier. In early March, Liss joined other young workers in testifying to Congress. Before the Congress members, she recounted this story as well as other observances of the strike and general treatment of Lawrence workers.

Women’s unique position as informal community organizers also played a vital role in the strike’s success. They operated kitchens, provided childcare, and helped leaders plan “children’s exoduses,” during which children of strikers were sent on trains to volunteer caretakers. Women-built networks across ethnicities created the essential united front needed to sustain a lengthy strike. These networks also became crucial communication tools as town leaders and mill owners restricted access to public spaces.

We stick together now, all of us, to bring about a settlement according to our ideals, our ideas of what is right.

Woman Mender and Striker

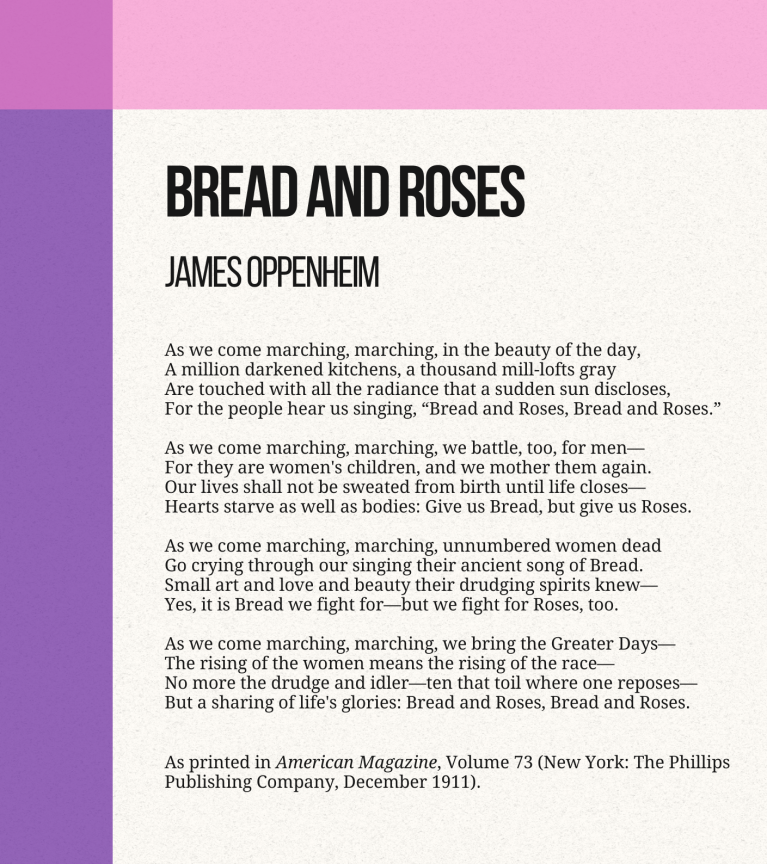

"Bread & Roses"

Inspired by suffragists and labor activists, James Oppenheim wrote the poem “Bread and Roses” in 1911. He attributed “Bread for all, and Roses, too,” to “a slogan of the women of the West” in the American Magazine. The phrasing had been seen by suffragists and labor organizers, such as Chicago women’s rights activists and social reformer Helen Todd. They recognized that work should provide both “bread” – money for the essentials of food, housing, and clothing– and “roses” – a sense of dignity and respect in work. Oppenheim echoed these sentiments in his poem.

In 1912, Lawrence strikers used “Give us Bread and Roses” as a rallying cry during the strike, with the strikers claiming the phrase as its name. In the same year, New York organizer and suffragist Rose Schneiderman also helped popularize the term during a speech in Ohio, “What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist…The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.”

Since the strike, the poem has been adapted and set to music several times, and it has long remained an anthem for both labor and women’s rights movements.

Question: What do the terms “Bread” and “Roses” mean to you?

"Bread and Roses" by the Radcliffe Pitches

The Radcliffe Pitches are Harvard University's oldest treble-voice a cappella group, founded out of Radcliffe College in 1975. The Pitches were founded with the mission of breaking down barriers and democratizing access to opportunities for women in the arts at Harvard, whose voices had long been marginalized. Through confidence building workshops, collaborations, and performances around the world, the Pitches continue to inspire and uplift, fostering a sense of community and celebration of music and the arts. The Radcliffe Pitches of Harvard University sang a rendition of "Bread and Roses" for a 2015 performance.

Results of the Strike

The strike brought Lawrence national attention. People from across the country demonstrated support. Sympathizers in New England towns and cities offered to host children. Student groups and professors from women’s colleges, including Smith, Mt. Holyoke, Wellesley, and Radcliffe, raised money for the strikers. Newspapers tracked strike events and gave negative publicity to the police and militia for their harsh treatment of strikers. As a result, Congress and the Bureau of Labor launched investigations into the more violent events of the strike.

In early March 1912, Josephine Liss testified during a hearing in front of the House of Representatives Committee on Rules. She spoke of a violent event that occurred during a Polish community strike meeting:

… Then another policeman came over to me—there was about four or five. He says 'Tell these people, in your own language, not to block up the sidewalk.' … He took a walk and came back again, and one of the fellows was standing on the sidewalk... This policeman grabbed him and arrested him. … the rest of the people came out from the hall, and in about five minutes there were about 20 policemen clubbing people, and they were clubbing the women, and they threw one woman in the mud. She was about 45 years of age. Another woman fell down and they hit her head. They split their heads open. I seen blood shed there."

After nine weeks, mill owners began to cave to strikers. Pacific Mill and the American Woolen Company agreed to most demands on March 12, 1912. Other companies followed suit throughout the month. 15,000 strikers voted to accept the companies' offers and end the strike on March 14.

At the end of the day, striking workers in Lawrence succeeded in receiving wage increases from 5-25%. Across New England, textile workers received wage increases of 5-7% as a result of the strike. Partially as result of this strike, the Massachusetts legislature also passed a law that established a wage committee to investigate raising the minimum wage for women and children.

The women won the strike.

Bill Haywood, IWW Labor Leader

Disconnecting New England: The 1919 Telephone Operators Strike

Organizing within the Women’s Trade Union League

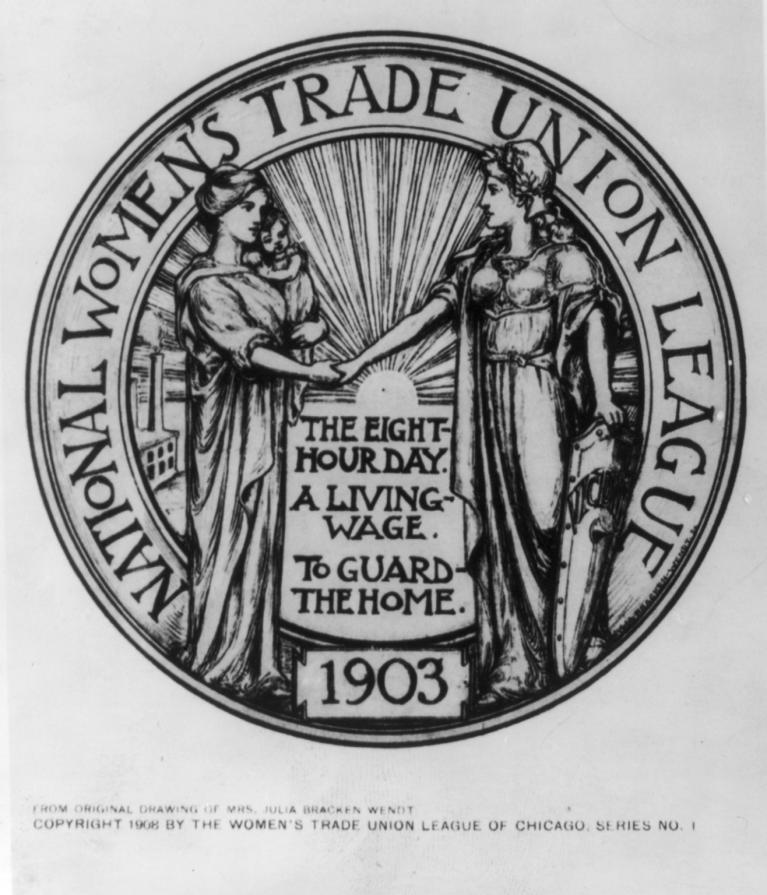

Much like the mill workers of Lawrence, other women workers in Massachusetts activated the power of labor unions in the early 1900s. In 1903, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) hosted their annual meeting in Boston’s Faneuil Hall. During this meeting, a group of national women labor leaders and social reformers, including Mary Morton Kehew, Mary Kenney O’Sullivan, and Chicago’s Jane Addams, founded the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL).

Nationally, working women used the WTUL as a tool to organize for better rights and conditions. Governance in the League included a 50/50 split in board representation between middle/working class members and their upper class allies. While this structure sometimes led to internal conflict among members, the WTUL often proved to be a strong cross-class alliance of women.

The Boston Chapter of WTUL grew quickly as it connected working women to the larger labor movement in Boston. Consisting of about 4,000 members by 1919, the league served a variety of workers in different fields. Telephone operators in particular were a key demographic of the membership.

Boston Telephone Operators Unionize

At telephone exchanges, telephone operators connected people regionally and nationally. They sat in front of telephone switchboards, receiving calls and patching them through to the correct location. Although the first operators were men, telephone companies began hiring women in the late 1870s and early 1880s. Women in these positions had to follow strict rules on dress and appearance, could not talk to each other while at their switchboards, and had to keep up with the fast pace for long hours without breaks. All the while, they were paid less than what men had earned in these positions.

WTUL worked with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) to establish the Boston Telephone Operators’ Union in 1912. This provided women operators an avenue to organize for their specific needs, including higher wages and better schedules and working conditions.

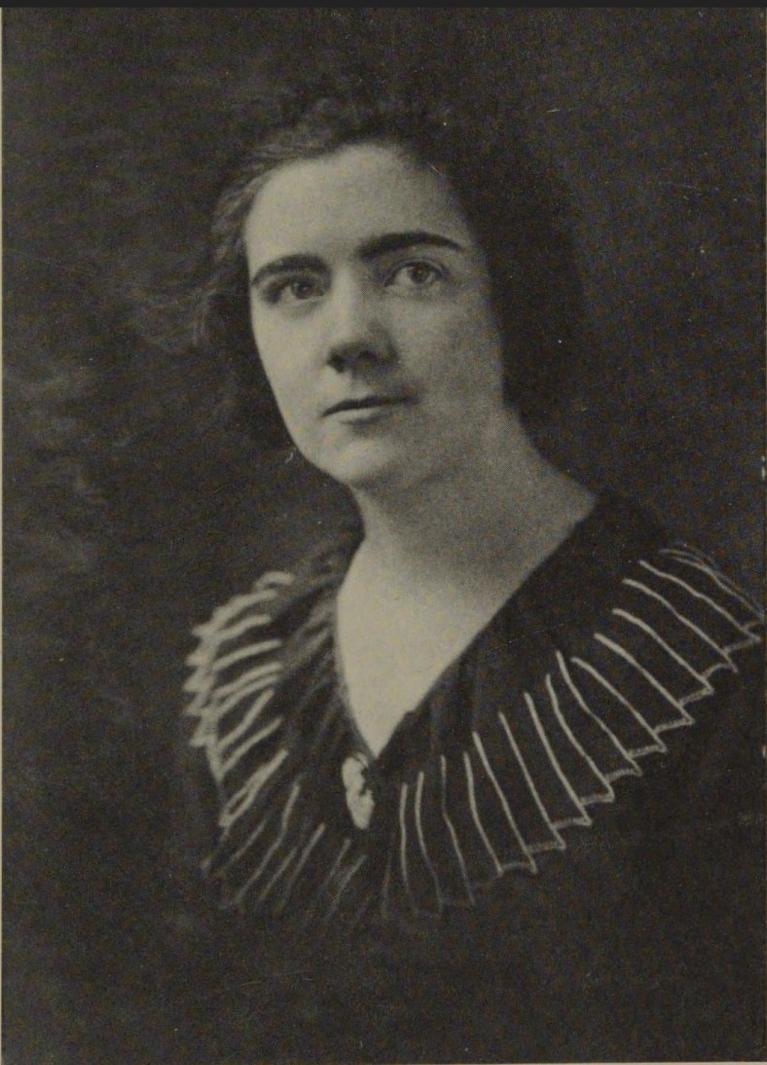

Profile: Julia O'Connor

Julia O’Connor was one of the main leaders during the 1919 Telephone Operators’ Strike. Born in Woburn to Irish immigrants, Julia O’Connor grew up working class and became a telephone operator in Boston shortly after graduating from high school in 1908. O’Connor was one of the charter members of the Telephone Operators’ Union and soon after joined the Boston WTUL. She became the first working woman to serve as president of BWTUL in 1915. In 1918, O’Connor served as the first president of the IBEW’s new Telephone Operators’ Department, the country’s first international union with women officers.

During this time, Julia O’Connor represented workers on the Massachusetts Minimum Wage Commission, which determined minimum wage rates for women retail workers. She was also appointed to an advisory committee for Postmaster General Albert Burleson. From this position, O’Connor saw Burleson’s disregard for telephone operators and his refusal to give them living wages. As a result, she resigned from the advisory committee in protest in January 1919, declaring:

“Wages of telephone operators and mechanics, particularly the former, have generally been below a living level. No statement on the telephone situation would be honest and complete if it failed to draw attention of the Post-office Department to the widespread discontent and unrest that exist among the telephone workers. The most obvious reason for this general restlessness has been the uncertainty and vacillation attendant upon the granting to them of needed and long-awaited increases in pay.”

Telephone Operators Go on Strike

In 1919, members of the Boston WTUL tried to negotiate with Postmaster General Albert Burleson for better wages and schedules. After several failed negotiation attempts, Boston operators lost patience. WTUL hosted a mass meeting in Faneuil Hall on April 11, 1919 during which operators voted to go on strike. At 7am on April 15, telephone operators walked out of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company building on Oxford Street in downtown Boston.

Strikers took to the streets, parading through downtown Boston. With the help of the WTUL and Boston Telephone Operators Union, they held meetings at Faneuil Hall and Boston Common and organized pickets around the clock.

Telephone operators received wide support for their strike. Janitors, elevator operators, hotel workers, and other workers aligned themselves with the operators. Cab drivers refused to drive strikebreakers to telephone exchanges. Police officers ignored calls to arrest the strikers. Soldiers returning from war and other male allies offered to take night shifts for picketing. Local newspapers mostly voiced approval of the strike.

Strike leaders – including Julia O’Connor, Mary Mahoney, and others – held firm as elected officials, telephone company executives, and male labor leaders called on them to end the strike without attaining their demands.

New England Disconnected

The absence of the telephone operators was immediately felt across New England. As news of the strike spread, operators at exchanges beyond Boston left their jobs and also went on strike to add their support. Even some men workers at exchanges also began striking. Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont all lost phone service, affecting thousands of people.

Victory in Days

Due to the significant disruption caused by the strike, Postmaster Burleson conceded to the strikers’ demands after five days. He allowed the New England Telephone Company to negotiate directly with strike leaders. Operators across Massachusetts and New England won a weekly pay increase from $16 to $19, better schedules, and recognition of their right to unionize.

The victory of the New England operators was not accomplished in the few days on the battle line. It had been accomplished in the patient years before, while an organization of character, strength, and of purpose was being built up.

Julia O'Connor

Even with these gains, the victories of the telephone workers did not last long. Subsequent failed strikes and improving telephone technology resulted in continued obstacles for telephone workers. Regardless, the Telephone Operators Strike showed the power of women-led union organizing to support women’s calls for better compensation.

"To be recognized with dignity": Rights for MA Domestic Workers

Women and the Workforce

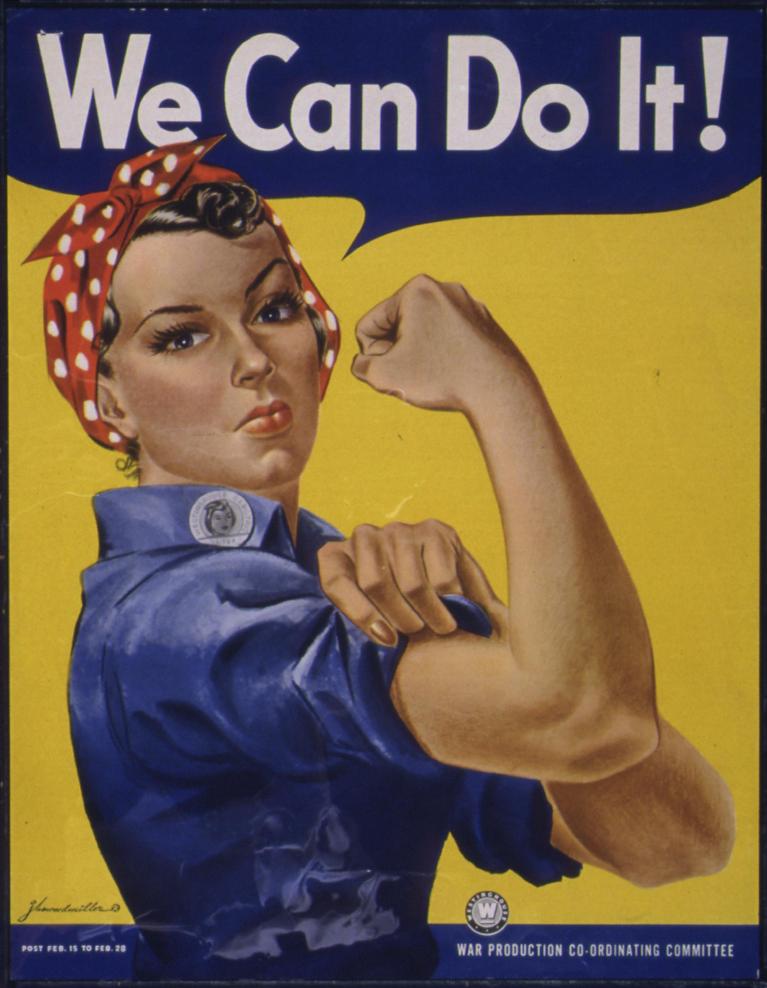

If it shall become necessary to employ women on work ordinarily performed by men, they must be allowed equal pay for equal work.”

- National War Labor Board, 1918

By the time the War Labor Board announced this recognition of “equal pay for equal work,” women had already been quite aware of the discrepancy in compensation between men’s and women’s labor. The World Wars, however, shed new light on the inequity of compensation for labor. Women who took over men’s jobs during the war effort showed that they were quite capable of performing traditionally “men’s work.”

Questions: Are there jobs today that are still perceived as “men’s work” or “women’s work”? Why or why not?

This pivotal moment helped make “Equal Pay” a rallying cry for working women as they faced the post-war era. Despite some advancements, employment barriers remained. Women continued to be paid less than men in most fields. And in the case of jobs traditionally considered women’s labor, such as domestic work and secretarial work, the need to dignify and justly compensate women for their labor remained.

In the second half of the 20th century, Boston-based activists responded to the call for change, making strides to ensure better treatment for these workers. For both domestic and secretarial work, these women’s actions extended beyond their communities, taking a prominent role in growing movements or building their own. Today, successive generations continue to build upon their victories.

Domestic Labor in the US and Massachusetts

Since the beginnings of the family economy, domestic labor – work conducted in the home – has been assigned to women. Women performed household responsibilities and took care of children and other dependents. They performed this work without compensation and recognition.

Question: In your family, who completes household chores and takes care of others?

When domestic work became professionalized in the 1800s, most workers were women. In the Northeast, including Massachusetts, domestic workers of the 1800s were mostly white European immigrants. This began to shift in the early 1900s with changes in immigration patterns and the migration of Black Americans from the South to northern cities.

Regardless of location, domestic work remained one of the few employment options for Black women. For this reason, Black women’s representation in the field grew, jumping from 28% of domestic workers in 1900 to 60% in 1950.

Of course, you could get domestic work, because they always felt that black people should do domestic work….The only resort for most black people was domestic work….That’s how they educated their families and did everything else…

Melnea Cass

Due to domestic workers’ gender identity, class, race, ethnicity, immigration status, or some intersection of these identities, they remain undercompensated for their labor.

Historically, domestic workers were excluded from 1900s legislation about workers’ rights. This meant employers were not required to follow minimum wage laws or give domestic workers paid time off, paid sick leave, or appropriate compensation for overtime. As a result, these workers often faced mistreatment, exploitation, and unjust compensation. In some cases, this mistreatment continues today.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a small community organization in the South End of Boston saw the unjust treatment of domestic workers and decided to take action. Its leader, the formidable activist Melnea Cass, forged a path forward to ensure domestic workers received the protection, compensation, and dignity they deserved.

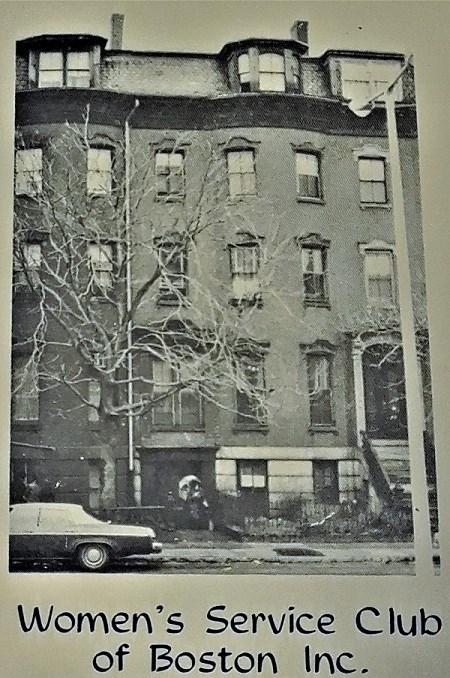

Melnea Cass and the Women’s Service Club

Formally incorporated in 1919, The Women’s Service Club of Boston (WSC) quickly became a South End institution. It served as an affordable shelter and community space for female workers, migrants, and college students. Led by Black women, the Women’s Service Club provided a variety of services and helped a broad range of individuals in Boston.

When Melnea Cass took the helm as president of the WSC in 1962, she already had decades of community organizing and activism under her belt. During her tenure, the WSC put significant resources towards helping domestic workers, most of whom were from the South or the Caribbean. The Club started the In-Migrant Training Program, which offered training, counseling, and housing for these migrants and immigrants.

The In-Migrant program proved a success, and the WSC received federal funding to further develop training programs. The Homemakers Training Program provided legal education, social services, and certification for domestic workers to receive a higher wage and social security benefits.

Many are still working for a pittance and being treated as nothing. We want to change all that…The domestic worker must be recognized as skilled labor and given fair wages and proper hours.

Doris Howard, director of Homemakers Training Program

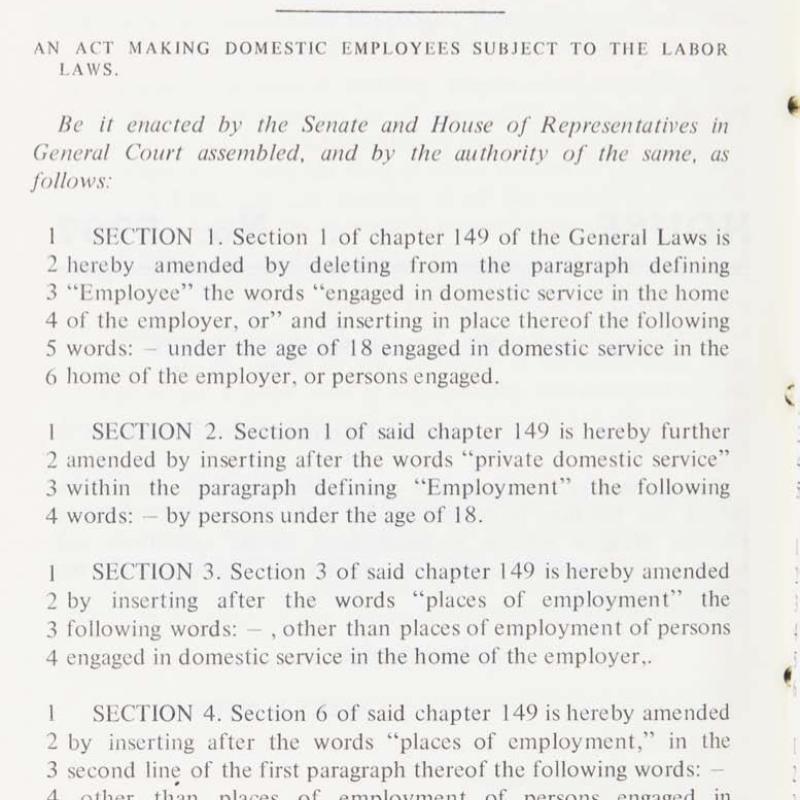

Cass and WSC members also worked on legislative proposals to address some of the unjust treatment and inequity that domestic workers faced. Starting in 1967, they convened conferences of domestic workers from across Massachusetts to hear primary concerns and issues faced on the job. They took into account significant issues facing domestic workers: receiving little pay for their long hours, working in poor conditions, performing duties beyond their job description, and facing instances of harassment. These conferences laid the foundation for petitions and legislative proposals sent to state legislators seeking their support for laws to secure better rights and legal protections for domestic workers.

Profile: Melnea Cass

Belovedly called the “First Lady of Roxbury,” Melnea Agnes (Jones) Cass stood as a pillar in the Boston community. She dedicated decades of her life to public service and advocating for others.

Born in Virginia, Melnea came to Boston at a young age with her family. She worked for several years as a domestic worker in Cape Cod and Boston, experiences she carried with her in later advocacy work. She married Marshall Cass in 1918 and had three children.

Melnea Cass’s first foray into activism was through women’s suffrage. She learned about the suffrage movement from her mother-in-law, Rosa Brown, and became among the first women in her neighborhood to register to vote in 1920.

Throughout her life, Cass worked tirelessly on behalf of others. At various points, she led the local chapter of NAACP, served as president of the Women’s Service Club, and chaired the Mayor’s Advisory Committee for Affairs of the Elderly. She also held leadership roles in Action for Boston Community Development (ABCD), Freedom House Inc., the South End Settlement House, and other local organizations.

When asked about her accomplishments, Melnea Cass considered her work organizing for domestic workers among the most significant in her life.

So many black women had done domestic work, and they hadn't been able to be recognized with dignity, and we brought that about.

Melnea Cass

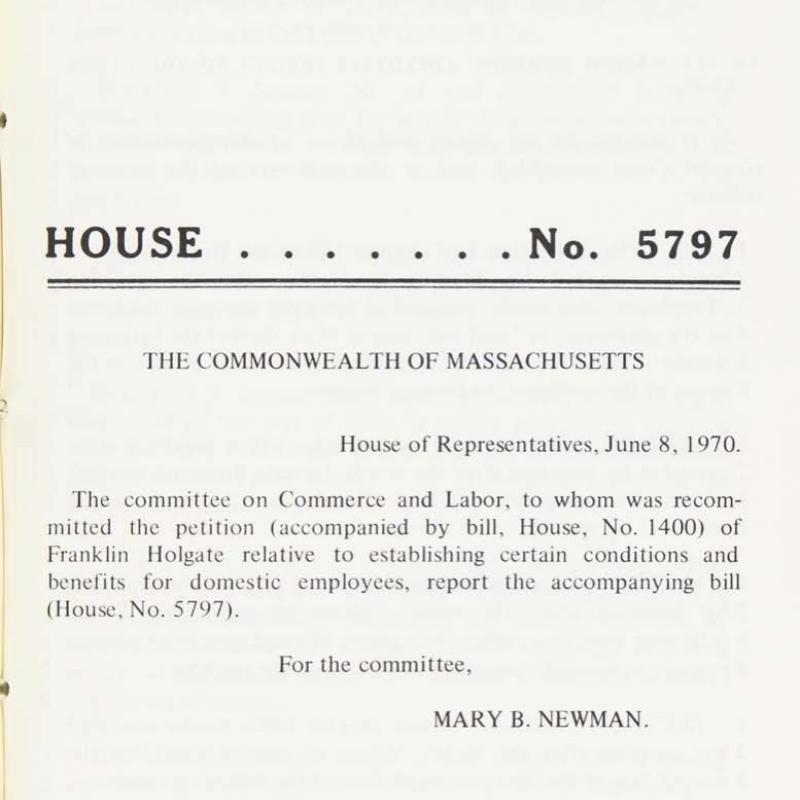

Victories and Leadership in the Domestic Workers Movement

Successfully organizing domestic workers across Massachusetts, the Women’s Service Club took their concerns to the State House. Their campaigning and petitioning led to legislative success. In 1970, the Commonwealth passed a law including domestic workers in state labor protections. Domestic workers achieved the right to minimum wage and overtime pay, access to unemployment benefits and workers compensation, and the right to collectively bargain.

On August 11, 1970, Melnea Cass wrote to Massachusetts Governor Francis Sargent in support of the bill:

On your desk is House Bill #5797 to be signed. It is a product of the Women Service Club’s very diligent and consistent efforts to make this a reality. We have sponsored projects to assist those women and men, especially black, who for many years were relegated to household work because of discriminatory practices, customs, etc. They were exploited as you know. We are determined that this shall pass away and that these forgotten workers will share in the benefits of all other workers especially in their categories. Will you please sign this bill and give the Women’s Service Club the honor of being present with you for a picture which will be history for many people, especially black women who will be affected.”

Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and New York were the first states to codify legislative protections for domestic workers. These laws, along with advocacy work, paved the way for an amendment to the federal Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) in 1974. After previously excluding domestic workers in labor protections for minimum wage law and overtime, among other protections, the 1974 amendment finally righted this wrong. Nationally, domestic workers now had to be paid at least minimum wage.

Melnea Cass Quote

Hear Melnea Cass reflect on working for domestic workers' rights.

"Melnea Cass." Interview by Tahi L. Mottl. February 1, 1977. Black Women Oral History Project Interviews, 1976–1981. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Melnea Cass and members of the Women’s Service Club stood alongside other leaders of the national domestic workers movement. Their community training programs and legislative victories became models for organizers across the country. They also participated in national gatherings in the domestic workers movement. In 1971, Cass and other WSC members attended the National Association of Household Employees and helped found the Household Technicians of America.

Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights & Ongoing Work

In the decades since the first legislative victories for domestic workers, other organizations have followed in the footsteps of Melnea Cass and the Women’s Service Club.

In 2010, the Massachusetts Coalition for Domestic Workers (MCDW) formed to advocate for better rights for domestic workers. Through collective action, MCDW effectively campaigned for the Massachusetts Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in 2014. One of the first of its kind in the country and the most expansive, the Bill of Rights ensures protections for the over 50,000 domestic workers in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Massachusetts Domestic Workers Bill of Rights Signing, 2014

On July 2, 2014, Governor Deval Patrick signed S.2132, “An Act Establishing a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights.” Read the full text of the law.

Boston City TV.

Today, over 90% of domestic workers in the United States are women. And women of color, as well as immigrants, are disproportionately represented in domestic labor.

Despite legislative victories, domestic workers remain largely under compensated and exposed to mistreatment and discrimination. In Massachusetts, MCDW and its partner organizations continue to argue for better wages and protections for domestic workers.

9to5: Demanding Raises, Rights, and Respect

As activists advocated for domestic workers' rights, women working as secretaries in Boston's offices also began to call for change. They too lacked the pay and respect they deserved. Championing "Equal Pay for Equal Work," they created a national labor movement alongside the second wave feminist movement.

9to5 Beginnings

The origins of 9to5 look very familiar to a worker today – a group of friends and colleagues discussing (and complaining about) their jobs. But instead of resigning themselves to low pay, demeaning tasks, no upward mobility, and harassment, a group of women in 1972 decided to do something about it.

Their movement was of women, by women, and for women. All kinds of women found a home in 9 to 5. And maybe the way they organized could only have been done by women…

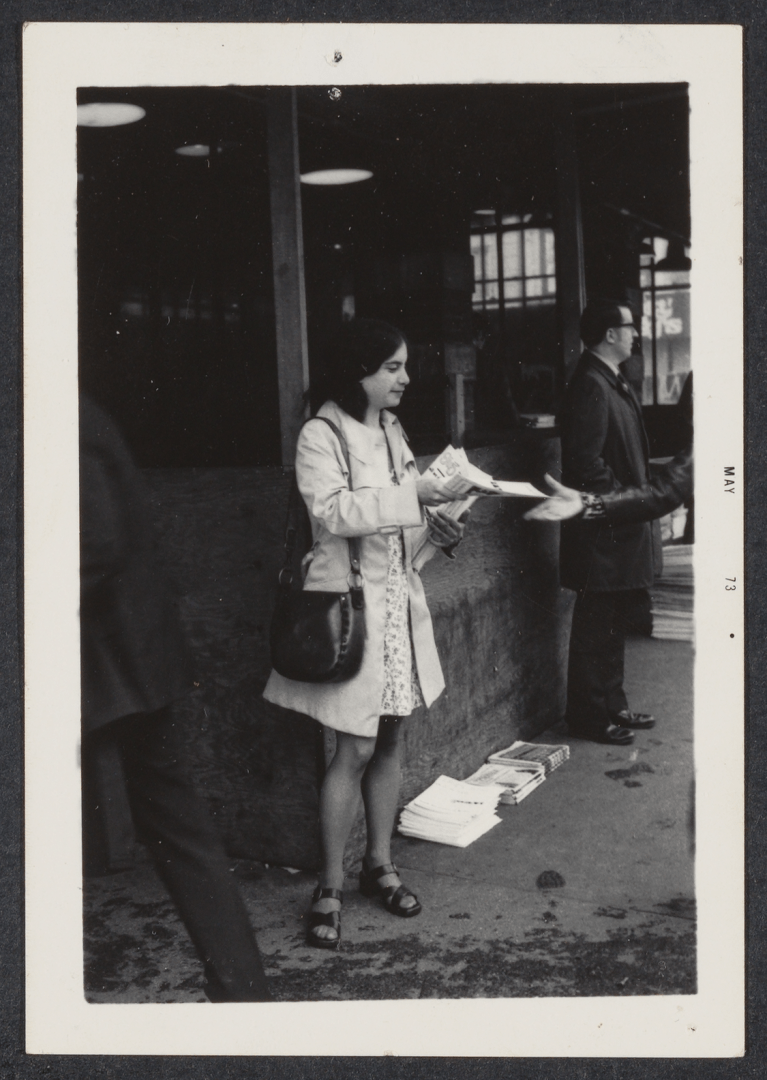

They met at watercoolers, during lunch hours, and sometimes after work with their children in tow. They used their telephones and typewriters to get the message out. They surveyed, leafleted, and petitioned. They lobbied and rallied. They confronted their employers and public officials to demand raises, rights, and respect. Their meetings, their leaflets, and their picket lines were not quite like anything seen before.

Jane Fonda

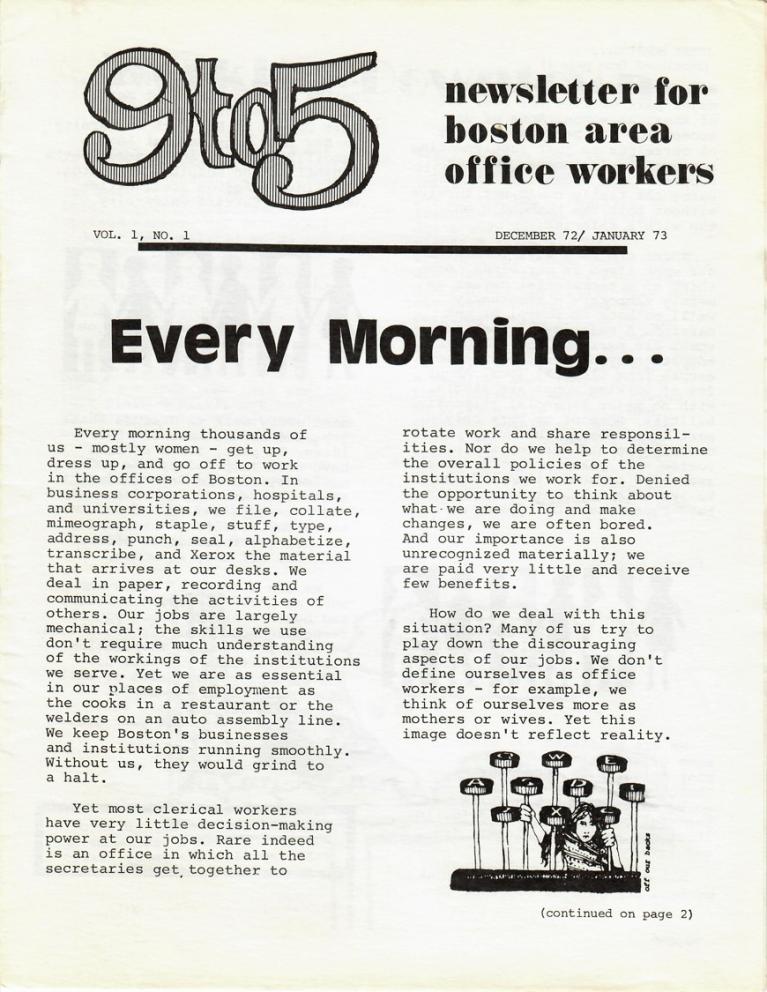

In the fall of 1972, a group of Harvard University office workers organized by Karen Nussbaum and Ellen Cassedy decided to address the disrespect they faced in their jobs. They established a newsletter for Boston office workers and began handing them out all around the city. Organizing slowly and methodically among office workers across the city, the group named itself 9to5, a play on the hours of most office workers.

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Read Transcript. (Courtesy of Ellen Cassedy)

Profile: Karen Nussbaum

Karen Nussbaum was no stranger to activism and organizing. She grew up in a socially conscious family and had participated in the anti-Vietnam War movement. With friend and fellow worker Ellen Cassedy, Nussbaum decided to organize her fellow office workers at Harvard. Little did she know she would help to found a national labor movement of women.

A successful organizer, Nussbaum took on several leadership roles in the 9to5 movement. As 9to5 in Boston grew into the national organization: 9to5, National Association of Working Women (“9to5”), she became the first director of the national 9to5. And when 9to5, National Association of Working Women successfully established its accompanying union, District 925 of SEIU, Nussbaum served as its first president.

After over two decades of work with national 9to5 and then District 925, Nussbaum went on to advocate for workers through other national leadership positions. She served as director of the Women’s Bureau in the Department of Labor during the Clinton Administration and later founded the Working Women’s Department in the labor union AFL-CIO. In 2003, Nussbaum became the founding director of Working America, a community labor organization and affiliate of AFL-CIO that advocates for non-union workers.

Profile: Ellen Cassedy

Discouraged and frustrated by her clerical job, Ellen Cassedy worked with her friend and colleague Karen Nussbaum to organize the Harvard University office workers. More comfortable behind the scenes, Cassedy helped build the foundation for what would become 9to5.

Early on, she attended a school for women organizers in Chicago called the Midwest Academy. There Cassedy learned the tools needed to develop this small community of Boston women into a movement. As 9to5 grew, Cassedy took on leadership positions. In Boston, she organized and led local and statewide efforts on behalf of office workers in banking, publishing, and other fields. When 9to5 went national, Cassedy became the director of the Washington DC office working on federal policy efforts.

After leaving 9to5, Cassedy focused on a career in writing. She served as a speechwriter for SEIU and later in the Clinton Administration. Cassedy has also written and translated an array of publications related to labor, history, and literature.

Today, it was no longer mill workers but office workers who held the low-paid, low-status jobs at the center of our changing economy. Maybe now it was our turn to add a link to the chain of social change that stretched back through the generations. And maybe I could be part of forging that link.

Ellen Cassedy

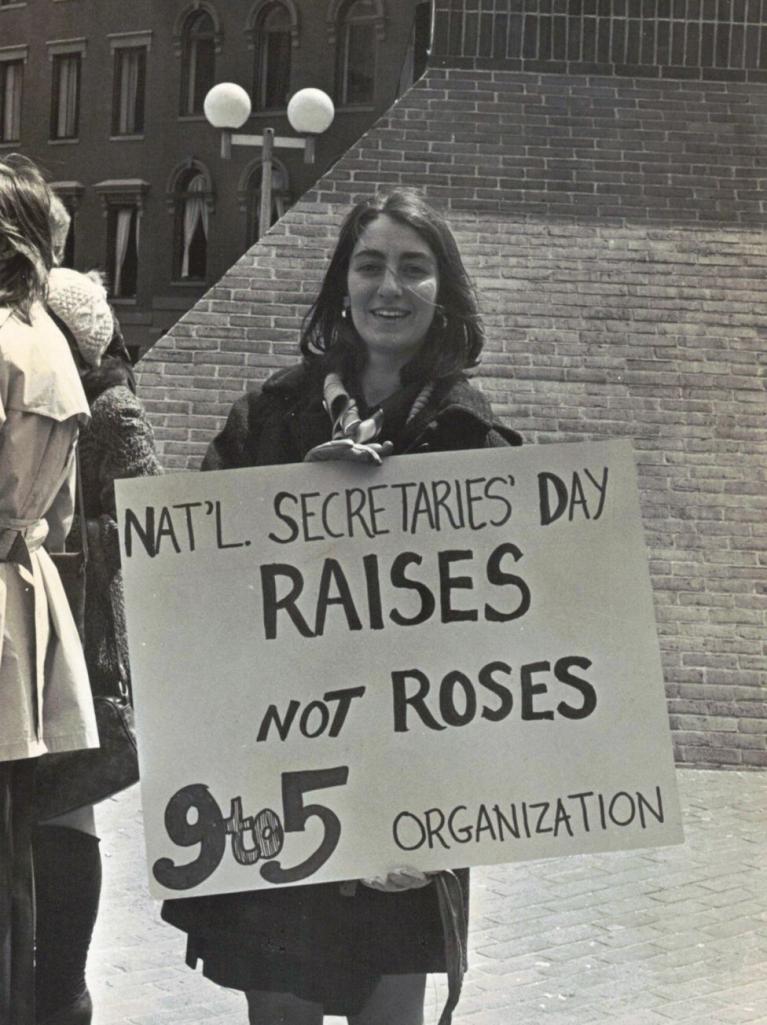

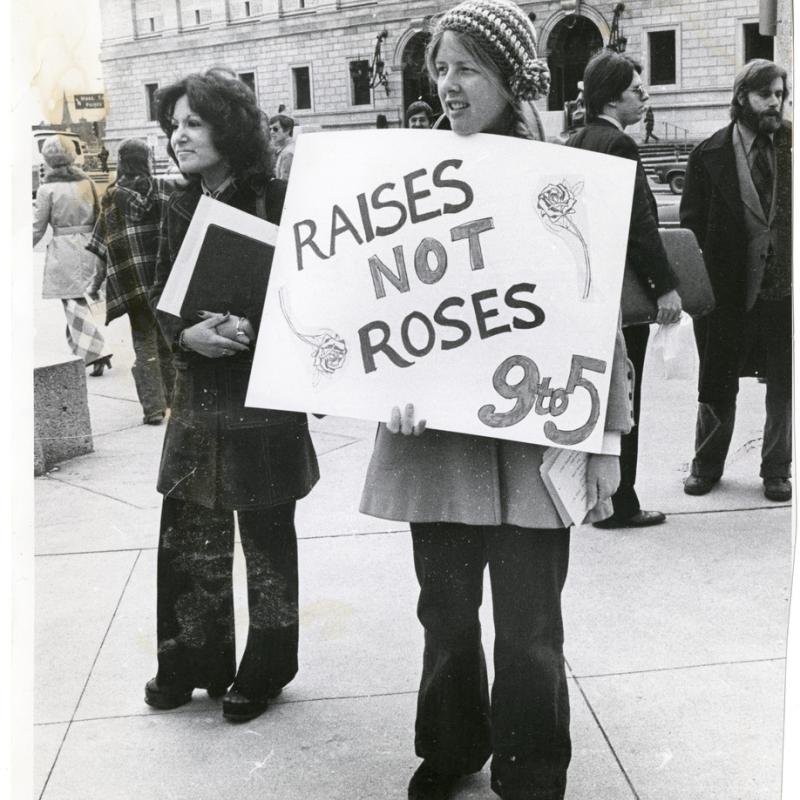

“Raises, Not Roses”

Just compensation and equal pay were among the first priorities for 9to5 organizers. According to co-founder Ellen Cassedy, “equal pay was the movement’s first rallying cry.”

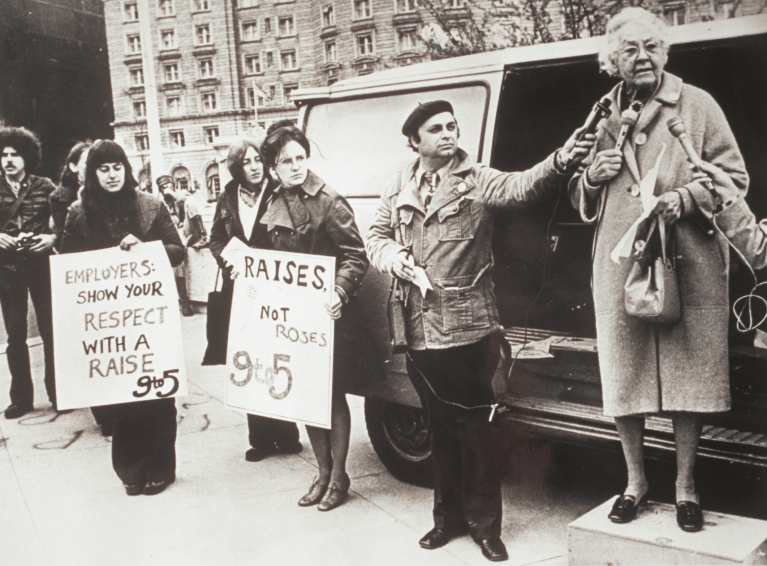

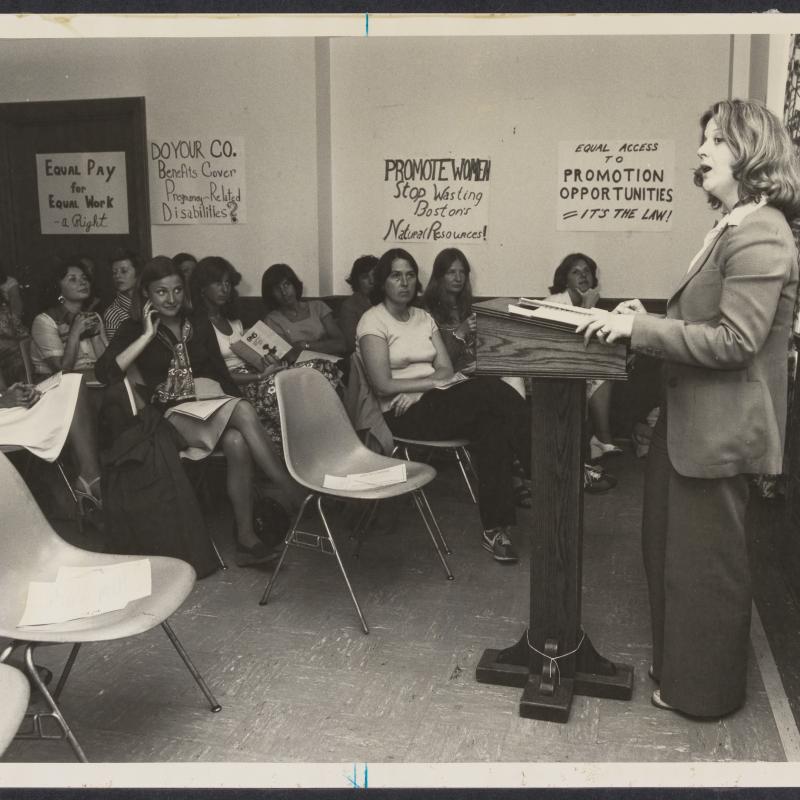

By 1974, 9to5 began hosting public events. These included public rallies, forums, and demonstrations. Women organizers also canvassed door-to-door and met with women individually. They listened to women’s stories of low pay and mistreatment in order to shed light on universal issues office workers faced.

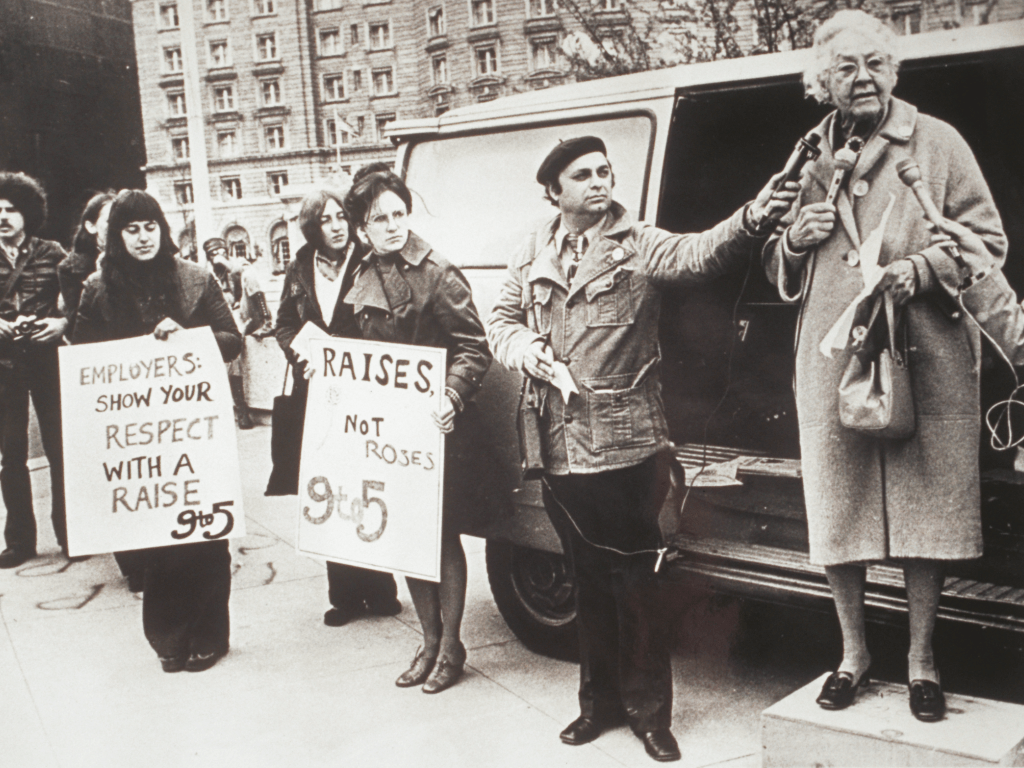

Former suffragist and lifelong activist Florence Luscomb speaks at 9to5's first outdoor rally in 1974. (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.)

Karen Nussbaum Quote

Hear from Karen Nussbaum on how 9to5 organizers approached listening to women's issues in the workplace.

From: "SEIU District 925 Legacy Project, Oral History Transcript: Ellen Cassedy, Karen Nussbaum, and Debbie Schneider." Interviewed by Ann Froines. November 1, 2005. Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

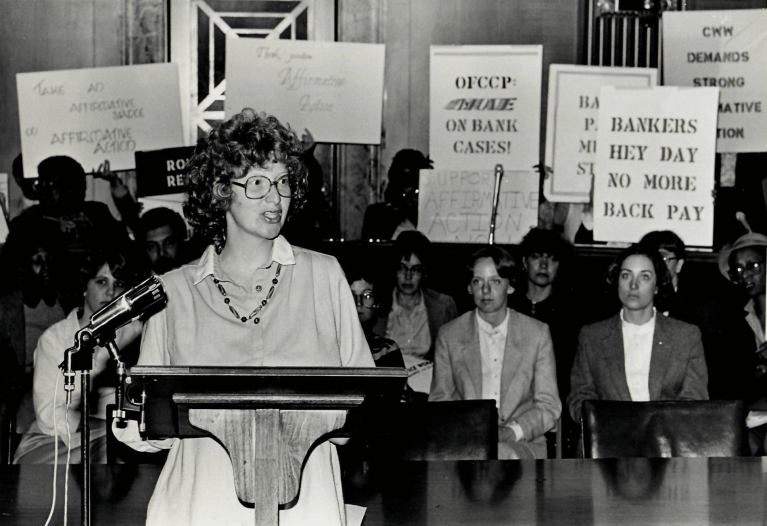

9to5 targeted particular companies for their poor treatment of office workers, picketing such companies as John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company and First National Bank. 9to5 women demanded changes in employment practices, pay, and working conditions.

While organizing on the ground level, 9to5 also went directly to government officials. They submitted petitions and provided testimony for officials on the state and national level. Working with Massachusetts Attorney General Francis Bellotti, 9to5 successfully forced a collection of major employers known as the Boston Survey Group to end its wage-fixing practices. 9to5 had argued that the Group had conspired to keep wages low for working women across the city. Their efforts resulted in an approximately 10% increase of wages for women office workers at companies across the city.

In Boston, 9to5 leaders also established a union with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU): Local 925 became a women-led entity within SEIU, one of the first of its kind.

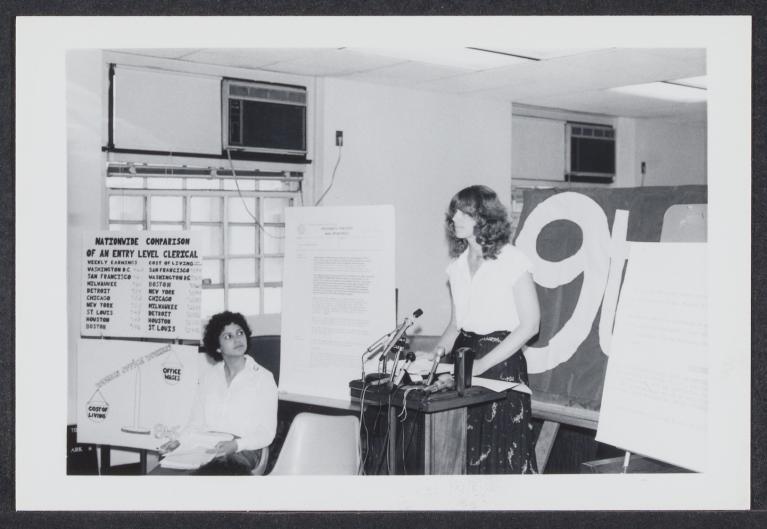

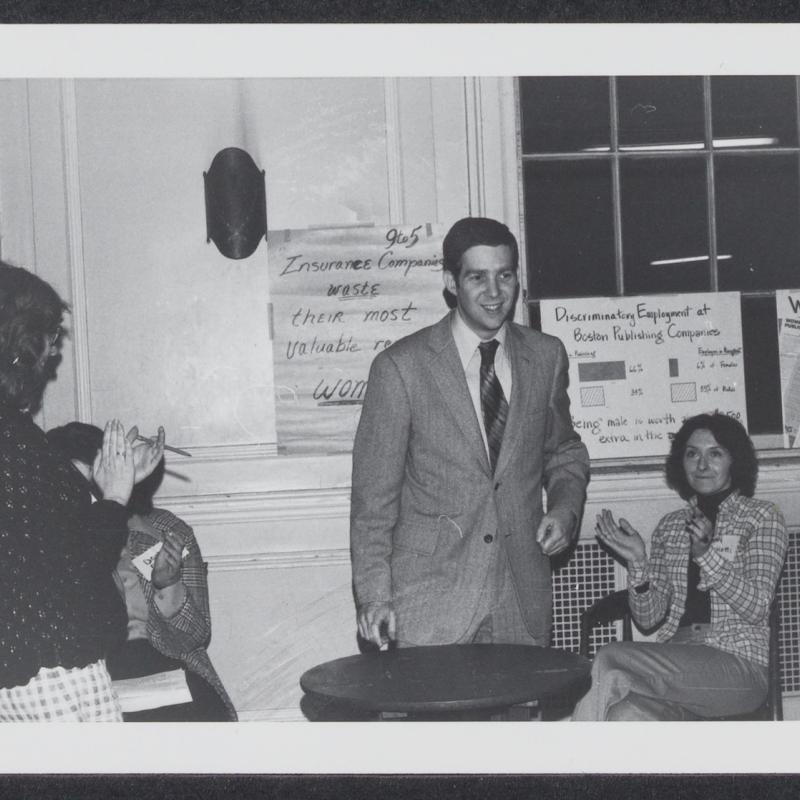

9to5 in Action

Members of 9to5 canvassed, held rallies and protests, organized meetings with women workers, and met with state and local officials. See the gallery below to understand the tactics 9to5 used to make change.

Question: What tactics do you see activists use today to advocate for their causes?

A National Organization and Union…of Women, by Women, and For Women

By 1976, 9to5 began to expand nationally, joining with similar organizations in New York, San Francisco, Cleveland, and Dayton. New chapters popped up in New England and beyond. Two years later, the national organization had been named “9 to 5, National Association of Working Women.” At its height, 9to5 members lived in 45 states.

9to5, National Association of Working Women Chapters

In 1976, Boston's 9to5 (blue star) began meeting with San Francisco Women Organized for Employment, Chicago Women Employed, New York Women Office Workers, as well as other 9to5 chapters in Dayton and Cleveland (blue circles), to align goals and strategies. In 1978, these organizations and 9to5 chapters joined to form 9to5, National Association of Working Women. 9to5 chapters (pink circles) continued to grow across the country into the 1980s.

What we wanted to do was, both build power for women on the job, but use the power of women to transform the labor movement.

Karen Nussbaum

Shortly after the organization went national, so too did the union. In 1981, organizers established District 925 within SEIU. Operating across the country, District 925 was a women-led union that could elect its own officers and hire its own organizers. At the height of the union, District 925 had 10,000 members across the country. It helped secure pay raises, opportunities for professional development, family health care benefits, paid leave, and child care for its members.

Karen Nussbaum Quote

Hear from Karen Nussbaum about forming a women-led organization and movement.

From: "SEIU District 925 Legacy Project, Oral History Transcript: Ellen Cassedy, Karen Nussbaum, and Debbie Schneider." Interviewed by Ann Froines. November 1, 2005. Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

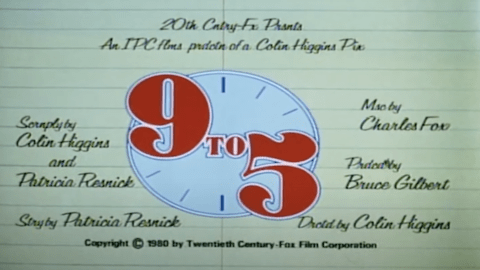

The movement also took root in American popular culture. Actor and activist Jane Fonda decided to produce a movie that highlighted the mistreatment of women office workers, albeit with a comedic twist. She and other producers met with 9to5 members in Cleveland, who shared their stories of facing demeaning jobs and harassment on the job. These experiences inspired elements of the 1980 movie 9 to 5, starring Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton.

The movie bolstered the message of the 9to5 movement, and organizers took advantage of this publicity. They hosted fundraisers and educational events across the country to coincide with the film’s release. As Karen Nussbaum recalled:

...we did a whole educational campaign around it. Jane Fonda went to a dozen cities, did events, and I went around the country, and did a 20-city tour called "The Movement behind the Movie." We figured out how we did this interplay between popular culture, public activism, and changing the public debate.”

9 to 5 Movie Trailer

"9 to 5" movie (1980) starring Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton.

Rotten Tomatoes Classic Trailers.

9to5 Today

Although union busting efforts forced it to dissolve in 2001, the union District 925 effectively gave a voice to women workers in the labor movement. It showed the important role unions can play in the fight to address the gender pay gap.

9 to 5, National Organization of Working Women remains active today with members in every state. The organization celebrated 50 years in 2023 of advocating for working women and families.

The Fight Continues…closing the Gender Wage Gap in the 21st century

In the 21st century, leaders and organizers in Massachusetts have continued to advocate for just and equal pay for women workers. In 2014, the Women’s Bar Association, Massachusetts Commission on the Status of Women, and MASSNOW formed the Equal Pay Coalition. This Coalition advocated for amendments to the 1945 Massachusetts Equal Pay Act, including clarifying the understanding of “comparable work” and prohibiting the practices of pay secrecy and using salary history during hiring. Through a collaborative and tireless effort, the Equal Pay for Comparable Work Law passed in 2016 and became effective July 1, 2018.

How far have we come and where do we go from here?

From Lowell factories to Boston offices, Massachusetts women workers laid the foundation for the ongoing struggle towards just and equal pay. Thanks to their activism, and the work of organizers and leaders today, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has remained a national leader in addressing equal pay.

Despite these legislative victories, Massachusetts still has significant work before it in order to accomplish full pay equity for women. Even with the existing equal pay laws in place, the Commonwealth still ranks 17th among states in gender pay parity (as of March 2021).

Women of color often face greater disparities in pay, signaling a need to develop legislation that specifically addresses intersectionality of wage gaps and pay inequity.

The cultural norms and expectations about women’s economic status, rooted in the notion of the family economy, also continue to contribute to how women’s labor is valued and compensated. Predominantly women-occupied fields, such as education and caregiving, are consistently undervalued and underpaid. These issues show the work that remains when it comes to dignifying and justly compensating women workers.

Coalitions, such as Wage Equity Now, and government-led initiatives, such as Equal Pay MA, are continuing to advocate for solutions that will address the gender wage gap, such as legislation, advocacy, and training to empower working women.

Question: How might we learn from the Massachusetts women who have come before us in addressing the issues that remain in equal pay?

Over the past two hundred years, women in Massachusetts have shown us the power of collective action in protesting unjust and unequal pay. With political savvy and skillful organizing, these women often made transformative change that echoed well beyond their towns and communities to across the region and even the country.

They were driven by their self-worth and their drive to receive adequate compensation for their work. May we be inspired by their desire to live a life not just with bread, but with roses too.

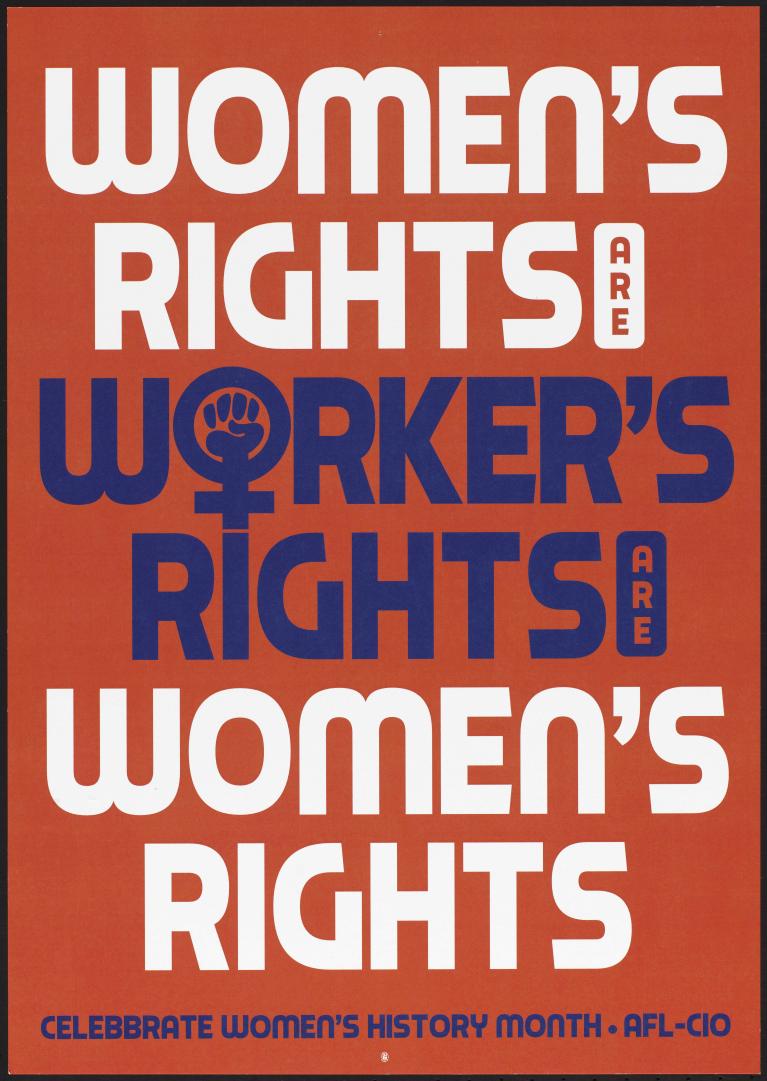

Stephen Lewis Poster Collection, Joseph P. Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Credits

Acknowledgements

Exhibit curated by Katie Woods, Digital Public Historian.

The Massachusetts Women’s History Center would like to give special thanks to the following individuals and institutions for their assistance: Ellen Cassedy; Karen Nussbaum; Janet Selcer; Dr. Mia Michael; Tom Cleary; Marcie Farwell and Melissa Holland, Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives, Cornell University; Carisa Kolias and Anthony M. Sampas, Center for Lowell History, UMass Lowell Archives and Special Collections; Amita Kiley, Lawrence History Center; Bridget Cooley, Lowell Historical Society; Lynn Public Library; Karin Carlson-Snider, Northeast Historic Film; Grace Millet, Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections; Grace Bida, The Radcliffe Pitches; Diana Carey and Jennifer Fauxsmith, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University; Morgan Wilson and Rebecca Chasse, University of New Hampshire Library; and Dawn Lawson, Molly Banes, and Sarah Lebovitz, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

General Labor and Equal Pay Works Cited

Blewett, Mary H. Constant Turmoil: The Politics of Industrial Life in Nineteenth-Century New England. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000.

Blewett, Mary H. We Will Rise in Our Might: Working Women's Voices from Nineteenth-Century New England. Cornell University Press, 1991.

Brady, Dorothy S. “Equal Pay for Women Workers.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 251 (1947): 53–60.

Calef, Anne. “The Stubborn Persistence of the Gender Pay Gap in Massachusetts.” Boston Indicators. March 31, 2022.

“Closing Greater Boston’s Gender and Racial Wage Gaps.” Boston Women’s Workforce Council Annual Report, 2021.

Cobble, Dorothy Sue. The Other Women's Movement: Workplace Justice and Social Rights in Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Cobble, Dorothy Sue. Women and Unions: Forging a Partnership. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993.

Cott, Nancy. Bonds of Womanhood: Woman’s Sphere in Early New England, 1780-1835. Yale University Press, 1977.

DeSimone, Bailey. “From the Serial Set: The History of the Minimum Wage.” LOC Blogs, Sept 3, 2020.

Dray, Philip. There is Power in a Union: The Epic Story of Labor in America. United States: Random House, Inc., 2010.

Enwemeka, Zeninjor. “How The Mass. Pay Equity Law Has — And Hasn't — Changed Things, 1 Year In.” WBUR, July 19, 2019.

Hallock, Margaret. “Unions and the Gender Wage Gap.” In Women and Unions: Forging a Partnership, edited by Dorothy Sue Cobble, 27-43. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993.

Hart, Vivien. Bound by Our Constitution: Women, Workers, and the Minimum Wage. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Hartford, William F. Where is Our Responsibility? Unions and Economic Change in the New England Textile Industry, 1870-1960. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1996.

Johnston, Katie. “A push to make pay more transparent, and equitable, in Mass.” Boston Globe. February 01, 2023.

Juravich, Tom, William Hartford, and James Green. Commonwealth of Toil: Chapters in the History of Massachusetts Workers and Their Unions. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. In Pursuit of Equity: Women, Men, and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in 20th-century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Kimball, Nina Joan. “Celebrating the Massachusetts Equal Pay Act.” Equal Pay MA. July 30, 2021.

LeBlanc, Steve. “Gov. Baker Signs Law Requiring Equal Pay For Comparable Work.” WBUR, August 1, 2016.

Leung, Shirely. “Gender Wage Gap widened after state passed equal pay law.” Boston Globe. July 14, 2022.

MacLean, Nancy. Freedom is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace. United States: Russell Sage, 2006.

“Massachusetts Equal Pay Coalition Celebrates Historic Signing of Pay Equity Legislation.” Women’s Bar Association. August 1, 2016.

Massachusetts Legislature. “An Act to Establish Pay Equity.” Session Laws, Acts (2016), Chapter 177. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2016.

Massachusetts Legislature. “Discrimination on basis of gender in payment of wages prohibited; enforcement; unlawful practices; good faith self-evaluation of payment practices.” General Laws, Part 1, Title XXI, Chapter 149, Section 105A. Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Murphy, Evelyn. Getting Even: Why Women Don’t Get Paid Like Men–and What to Do About it. New York: Touchstone, 2005.

Murphy, Margaret. “The Constitutionality of Minimum Wage: The Legal Battles of Elsie Parrish and Frances Perkins for a Fair Day’s Pay.” Princeton Historical Review. 2021-2022.

“New Equal Pay Coalition Files Comprehensive Pay Equity Legislation.” Massachusetts National Organization of Women. Accessed September 2023.

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration & Management. “Equal Pay for Equal Work.” U.S. Department of Labor. Accessed September 2023.

Office of the Attorney General. “Learn more details about the Massachusetts Equal Pay Act.” Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

“The Paycheck Fairness Act.” American Bar Association. Accessed September 2023.

The Termination Report of the National War Labor Board: Industrial Disputes and Wage Stabilization in Wartime. Volume 1. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1947.

United States Congress. “Equal Pay Act of 1963.” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

United States Congress. “Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009.” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

United States Congress. “Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Lowell Mill Girls Works Cited

Blewett, Mary H. The Last Generation: Work and Life in the Textile Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, 1910-1960. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1990.

Dublin, Thomas. Women at Work: The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826–1860. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Farley, Harriet. “Letter Written by Harriet Farley using the pseudonym ‘Susan.’” Lowell Offering, September 1844. Lowell Mill Girl Letters, UMASS Lowell Library. Accessed April 2023.

Fitzsimons, Gray. “Mill Life in Lowell, 1820 - 1880.” Center for Lowell History, UMASS Lowell Library. Accessed April 2023.

“Flare Up At Lowell.” Newburyport Herald, October 7, 1836, pg 2.

“I Cannot Be a Slave.” Lowell Historical Society: Digitized Song Sheets. University of Massachusetts Lowell Library Guides, October 15, 2020.

“Labor Reform: Early Strikes.” Lowell National Historical Park. National Park Service, October 26, 2021.

Larcom, Lucy. “Among the Lowell Mill Girls, A Reminiscence.” The Atlantic, November 1881.

“Lowell Female Labor Reform Association.” Lowell National Historical Park. National Park Service, October 26, 2021.

"Lowell History: Visitor Observations 1827-1913." University of Massachusetts Lowell Library, February 15, 2023.

"Lowell Mill Girl Letters." University of Massachusetts Lowell Library, January 20, 2024.

“Lowell Mill Women Create the First Union of Working Women.” AFL-CIO. Accessed April 2023.

“Lowell Turn Out.” Boston Morning Post, February 19, 1834.

Lucy Ann. “Letter from Lucy Ann, June 29, 1851.” Lowell Mill Girl Letters, UMASS Lowell Library. Accessed April 2023.

Moran, William. The Belles of New England: The Women of the Textile Mills and the Families Whose Wealth They Wove. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002.

Paul, Mary Stiles. “Letter from Mary Stiles Paul to Her Father, September 13, 1845.” Lowell Mill Girl Letters, UMASS Lowell Library. Accessed April 2023.

Robinson, Harriet Hanson. Loom and Spindle; or, Life among the Early Mill Girls. New York: Crowell, 1898.

“Sarah Bagley.” Lowell National Historical Park. National Park Service, April 27, 2021.

“The Merrimack River.” Lowell National Historical Park. National Park Service, November 9, 2018.

“The Mill Girls of Lowell.” Lowell National Historical Park. National Park Service, November 15, 2018.

“Turn out at Lowell,” Vermont Chronicle, February 28, 1834.

Ware, Norman. The Industrial Worker, 1840-1860: The Reaction of American Industrial Society to the Advance of the Industrial Revolution. United States: Quadrangle Books, 1924.

Weible, Robert, Ed. The Continuing Revolution. Lowell, MA: Lowell Historical Society, 1991.

“Women’s Activism in Lowell.” Lowell National Historical Park. National Park Service, August 12, 2022.

“Working People of Lowell.” Center for Lowell History, 2019. University of Massachusetts Lowell Library, January 17, 2024.

Lynn Shoeworkers Works Cited

“Best Foot Forward: The Shoe Industry in Massachusetts.” DPLA. Digital Exhibit.

Blewett, Mary. Men, Women, and Work: Class, Gender, and Protest in the New England Shoe Industry, 1780-1910. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

Blewett, Mary. “The New England Shoe Strike of 1860.” In We Will Rise in Our Might: Workingwomen's Voices from Nineteenth-Century New England, 76-85. United States: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Dawley, Alan. Class and Community: The Industrial Revolution in Lynn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976.

“Lynn Shoeworkers Strike.” MassMoments. Accessed April 2023.

Melder, Keith E. “Women in the Shoe Industry: The Evidence from Lynn.” Essex Institute Historical Collections 115, no.4 (October 1979): 270-287.

Prushinski, Rianon. “Lynn Shoemaker’s Strike.” Lynn Museum. April 16, 2021.

“The Bay State Strike: Movement Among the Women. Acts and Proceedings of Employers and Workmen. The Female Strikers at Liberty Hall.” New York Times, February 29, 1860.

The Boot and Shoe Industry in Massachusetts as a Vocation for Women. Boston: Women's Educational and Industrial Union, 1915.

“The Great New England Shoemakers Strike of 1860.” New England Historical Society. 2023.

“The Great Shoemakers’ Strike: Its origin and progress.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, March 17, 1860. 239-240.

“The Massachusetts Strike.: State of the Movement at Lynn--Mass Meeting of the Strikers at Lyceum Hall.” New York Times, March 2, 1860.

“The Massachusetts Strike.: The Females Afoot--Mistakes of the Strikers. Newspaper Accounts.” New York Times, March 03, 1860.

“The Massachusetts Strike.: The Ladies in Council--Speeches--Opposition to Reporters--Scenes Among the Women-- The Moon at its Full--Romance Disappears and Reality Commences--Three Thousand Men and Women in Procession--Incidents of the Day.” New York Times, March 9, 1860.

“The Shoemakers Still Striking.: The Hemmers and Stitchers in the Field-Feminine Spirit Aroused. Another Feminine Gathering. The Movement Elsewhere.” New York Times, March 1, 1860.

“The Strike of the Massachusetts Shoemakers: Particulars of the Movement-Its Origin and Progress.” New York Times, February 17, 1860.

“Ye Modern Rebellion.: Trouble in the Camp--Scenes Among the Leaders at Lynn--Strike, Striker, Strikest.” New York Times, March 06, 1860.

Lawrence Bread & Roses Works Cited

“Admits He Did Not Know Law: Lynch Unable to Give His Authority For…” Boston Daily Globe, March 6, 1912.

“Bayonets Disperse Women.: Several Knocked Down and Men Clubbed in…” The New York Times, February 22, 1912.

“Bread and Roses Strike Begins.” Mass Moments. Accessed April 2023.

Cameron, Ardis. Radicals of the Worst Sort: Laboring Women in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1860-1912. Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Dorgan, Maurice. Lawrence yesterday and today (1845-1918) a concise history of Lawrence Massachusetts - her industries and institutions; municipal statistics and a variety of information concerning the city. Lawrence, Massachusetts: Press of Dick and Trumpold, 1918. pgs. 66-74.

Flynn, Elizabeth Gurley. The Rebel Girl: An Autobiography, My First Life (1906-1926). United States: International Publishers, 1973.

Forrant, Robert. “The Real Bread and Roses Strike Story Missing from Textbooks.” Zinn Education Project. 2013. Accessed April 2023.

Forrant, Robert and Susan Grabski. Lawrence and the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike. United States: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

Lawrence History Center, University of Massachusetts Lowell History Department. “Bread and Roses Strike of 1912: Two Months in Lawrence, Massachusetts, that Changed Labor History.” Exhibitions. Digital Public Library of America.

“Lawrence History Timeline.” Lawrence History Center. Accessed April 2023.

“Lawrence Strike Comes to an End: Increased Wage Scale Accepted.” New York Times, March 14, 1912.

“Lawrence Strike Done.” Boston Evening Transcript, March 25, 1912.

Low, A. Maurice. “Woes of Strikers Told To Congress.” Boston Daily Globe, March 3, 1912.

Marcy, Leslie H. and Frederick Sumner Boyd. “One Big Union Wins in Lawrence.” International Socialist Review, April 1912. 613-630.

Marcy, Mary E. “The Battle for Bread in Lawrence.” International Socialist Review, March 1912. 533-544.

Moran, William. The Belles of New England: The Women of the Textile Mills and the Families Whose Wealth They Wove. United Kingdom: St. Martin's Press, 2007.

O’Connell, Lucille. “The Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912: The Testimony of Two Polish Women.” Polish American Studies 36, no. 2 (1979): 44–62.

Oppenheim, James. “Bread and Roses.” American Magazine, Vol 73, No. 2. New York: The Phillips Publishing Company, December 1911. pg. 214.

Sibley, Frank P.. “Lawrence’s Great Strike Reviewed: Cost $3,000,000, Lasted Nine…” Boston Daily Globe, March 17, 1912.

U.S. Bureau of Labor. “Report on strike of textile workers in Lawrence, Mass., in 1912.” Washington: Government Printing Office, 1918.

U.S. Congress. “The strike at Lawrence, Mass. Hearings before the Committee on rules of the House of Representatives on House resolutions 409 and 433, March 2-7, 1912.” Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1912.

Watson, Bruce. Bread and Roses: Mills, Migrants, and the Struggle for the American Dream. New York: Penguin Group, 2005.

Boston Telephone Operators Works Cited

“Aids the Girls.” Boston Daily Globe, March 14, 1904.

“Boston Girl Champion of Minimum Wage Bill.” Boston Daily Globe, April 21, 1918.

"Business Men Fail to Avert Tie Up Telephone Strike to Begin Today." Boston Daily Globe, April 15, 1919.

“Conference Today on Phone Strike.” Boston Daily Globe, April 13, 1919.

Deutsch, Sarah. Women and the City: Gender, Space, and Power in Boston, 1870-1940. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

"Employees Get Raise, Strike Ended Operators to Resume Work Today.” Boston Daily Globe, April 21, 1919.

Herwick III, Edgar B. “The More Things Change: 97 Years Ago, The Phone Company Was Also Dealing With A Strike.” GBH. Accessed May 2023.

“Into Unions: Women to be Organized.” Boston Daily Globe, March 21, 1904.

Lipartito, Kenneth. “When Women Were Switches: Technology, Work, and Gender in the Telephone Industry, 1890-1920.” The American Historical Review 99, no. 4 (1994): 1074–1111.

“Local Labor Notes.” Boston Daily Globe, February 15, 1915.

“Miss O’Connor Heads Telephone Union.” Boston Daily Globe, June 30, 1918.

"May Set Telephone Strike Date Friday.” Boston Daily Globe, March 29, 1919.

"May Vote Telephone Strike Tomorrow.” Boston Daily Globe, April 10, 1919.

“Misrepresentation laid to Burleson.” Boston Daily Globe. January 31, 1919.

Norwood, Stephen H. Labor's Flaming Youth: Telephone Operators and Worker Militancy, 1878-1923. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

“One Lone Operator Now on Duty at Brighton.” Boston Daily Globe. April 19, 1919.

“Phone Strike Will Start Tuesday A M.” Boston Daily Globe, April 12, 1919.

Sicherman, Barbara and Green, Carol Hurd. Notable American women : the modern period : a biographical dictionary. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1980. 525-526.

"Strike Paralyzes Phone Service Girls Get Appeal From White House.” Boston Daily Globe, April 16, 1919.

“Strike Situation in New England.” Boston Daily Globe. April 18, 1919.