Revolutionary Poet, Playwright, Historian

By Katie Woods, Digital Public Historian

While not as well-remembered as Massachusetts revolutionaries such as John Adams, Paul Revere, or even Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren had one of the most formidable political voices during the American Revolutionary era and the founding of the country.

Born on September 25, 1728, in Barnstable, Mercy grew up in the well-regarded Otis family. Her father, James Otis, was a respected lawyer and politician, and her mother, May Alllyne Otis, descended from pilgrims who arrived on the Mayflower. She was the third of 13 children; her closest older sibling was her older brother James Otis Jr. Although Mercy did not have access to formal education, James Jr. saw her interest in learning and, with their father’s support, she joined the young James’s tutoring sessions. When he left to study at Harvard University, he continued to send her reading recommendations to foster her intellectual growth. Through this informal learning, Mercy became interested in political thought and writing.

On November 14, 1754, Mercy Otis married James Warren, one of James Otis Jr.’s school friends. Mercy and her husband shared interests and philosophies, and James saw Mercy as an intellectual equal. They moved to Plymouth and had five sons: James (1757), Winslow (1759), Charles (1762), Henry (1764), and George (1766).

Through her family and husband, Mercy Warren became well-connected to the political leaders and thinkers of the time. In the 1760s, both James Warren and James Otis, Jr. became prominent figures who opposed British laws and policies meant to curtail the rights of colonists. Warren worked as an outspoken legislator and Otis popularized the phrase “taxation without representation is tyranny.” The Warren home became a center for revolutionary ideas, welcoming such figures as Samuel Adams, and John and Abigail Adams. As a witness and contributor to numerous conversations and strategy sessions, Mercy Otis Warren began to form her own political voice.

In the early 1770s, Mercy Otis Warren published several satirical plays in local Massachusetts papers. The Adulateur (1772), The Defeat (1773), and The Group (1775)—all published anonymously—criticized British policies and satirized British officials and Loyalists while glorifying the patriot cause. These plays received a great deal of attention. At the request of John Adams, Mercy Otis Warren wrote the poem “The Squabble of the Sea Nymphs, or the Sacrifice of the Tuscaroroes” (1774) about the Boston Tea Party:

The Virtuous Daughters of the Neigh’bring Mead

In Graceful smiles Approve the Glorious deed,

And ’tho the Syrens left their Coral beds,

Just or’e the surface, lifted up their Heads,

And sung soft peans, to the Brave and Fair”

Throughout the American Revolutionary War, Mercy Otis Warren supported her husband, who held several political and military positions, including President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and Paymaster General for the Continental Army. During the Siege of Boston (1775-1776), she often traveled between Plymouth and Watertown, where the Provincial Congress met. Warren sometimes served as her husband’s private secretary, while also recording significant events and maintaining active correspondence with leading revolutionaries, such as John and Abigail Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton.

Warren also kept writing and publishing. She is believed to have authored two more anonymously published satirical works, The Blockheads of Boston (1776) and The Motley Assembly (1779), both criticizing Loyalists. Her 1784 work, The Ladies of Castile (1784), centered on women in revolutionary Spain, a subtle nod to giving women more recognition for their contributions to revolutions.

Following the end of the Revolutionary War, Mercy Warren watched the formation of the new government for the young United States of America. However, she, like other Anti-Federalists (and later Democratic-Republicans), believed too much power was being placed with the federal government and not enough with the people themselves. In 1788, Warren wrote a series of pamphlets (published anonymously) called “Observations on the New Constitution, and on the Federal and State Conventions.” In these widely-distributed pamphlets, Warren criticized the newly adopted Constitution and called for individual rights and liberties to be more explicitly stated. These widely-distributed pamphlets likely helped prompt the creation of the Bill of Rights.

Mercy Otis Warren’s life was not without tragedy. Her brother James Otis Jr. never recovered from a 1769 physical attack by a British customs agent, and he struggled with mental health issues until he was killed by a lightning strike in 1783. While her sons all lived to adulthood, Charles (d. 1785), Winslow (d. 1791), and George (d. 1800) preceded her in death.

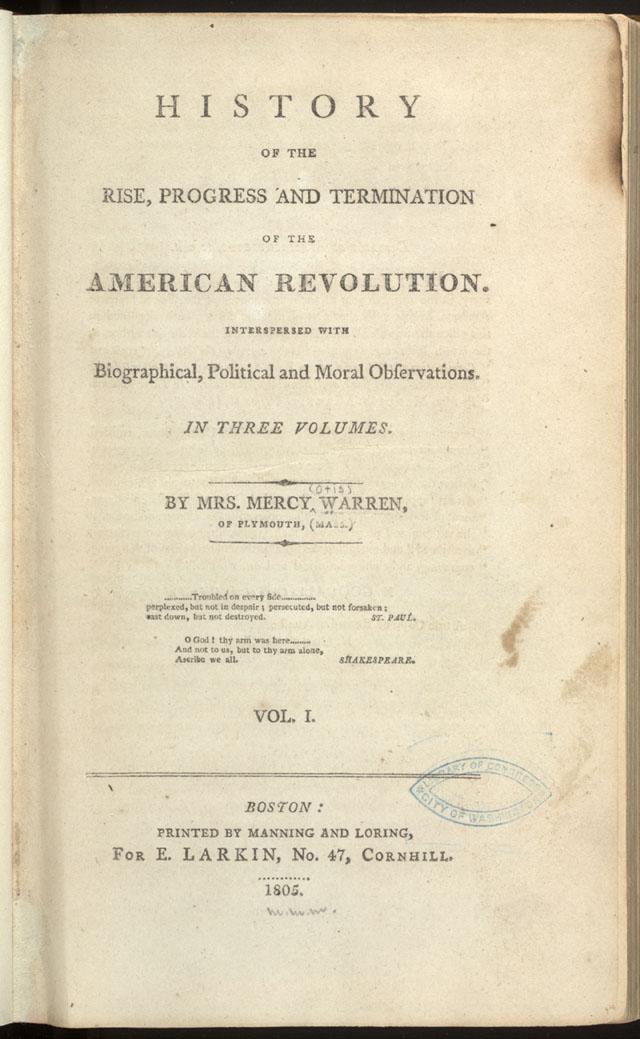

Due to these tragedies, as well as personal illness, Mercy Warren struggled to focus on her writing. She published a book of poems in 1790—the third woman in America to do so after Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley—-and continued to work on her history of the American Revolution. With the help of her eldest son, James, she published a three-volume History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution (1805). This was among the first nonfiction works published by a woman in America and one of the first comprehensive histories of the American Revolution.

In Warren’s History, she examined the causes of the Revolutionary War and recounted major events, either through personal recollections or by referencing contemporary sources. Warren also commented on the inhumanity of the institution of slavery and detailed the harm Indigenous tribes faced during the revolutionary era. She ended by reflecting on the legacy of the Revolution and the future of the country:

The principles of the revolution ought ever to be the pole-star of the statesman, respected by the rising generation…The people may again be reminded, that the elective franchise is in their own hands; that it ought not to be abused, either for personal gratifications, or the indulgence of partisan acrimony.”

While some lauded the work, such as Thomas Jefferson, others found her rendition too biased. In particular, John Adams felt she slighted him as she accused him of forgetting “the principles of the American revolution” because of his strong Federalist stance. With the help of Abigail Adams, they eventually reconciled in 1812.

After a life dedicated to patriot ideals, Mercy Otis Warren passed away on October 19, 1814. Today, her hometown of Barnstable honors her with a bronze statue on the lawn of the Barnstable County Courthouse (dedicated in 2001) and a “Mercy Otis Warren Cape Cod Woman of the Year Award,” launched in 2002.

Additional Resources

“Mercy Otis Warren.” Boston Women’s Heritage Trail. Accessed September 2025.

“Mercy Otis Warren Cape Cod Woman of the Year Award.” Barnstable County Cape Cod Regional Government. Accessed October 2025.

“Mrs. James Warren (Mercy Otis).” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accessed August 2025.

Raphael, Ray. “The Righteous Revolution of Mercy Otis Warren.” In The American Revolution. Edited by Carol Berkin. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Accessed September 2025.

Zagarri, Rosemarie. A Woman’s Dilemma: Mercy Otis Warren and the American Revolution. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2015.

Bibliography

“Biographical Sketch: Mercy Otis Warren Papers.” Massachusetts Historical Society. Accessed September 2025.

Bohrer, Melissa Lukeman. “Her Pen as Sword: Mercy Otis Warren.” In Glory, Passion, and Principle: The Story of Eight Remarkable Women at the Core of the American Revolution (New York: Atria Books, 2003), 93-123.

Herring, Danielle. “Mercy Otis Warren: The Secret Muse of the Bill of Rights.” Library of Congress Blogs. December 15, 2022. Accessed September 2025.

King, Martha J. "The ‘pen of the historian’: Mercy Otis Warren's History of the American Revolution." The Princeton University Library Chronicle 72, no. 2 (2011): 513-32.

Laska, Vera O. "Remember the ladies": Outstanding Women of the American Revolution. Boston: Commonwealth of Massachusetts Bicentennial Commission, 1976.

Michals, Debra. “Mercy Otis Warren.” National Women’s History Museum. Last updated 2015. Accessed September 2025.

Mikell, Patricia. “Mercy Otis Warren (1728-1814)” Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed 2025.

Stuart, Nancy Rubin. The Muse of the Revolution: The Secret Pen of Mercy Otis Warren and the Founding of a Nation. Boston: Beacon Press, 2008.

Warren, Mercy Otis. “Enclosure: Poem on the Boston Tea Party, 27 February 1774.” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, December 1761 – May 1776. Edited by Lyman H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963, pp. 100–103.]

Warren, Mercy Otis. History of the rise, progress, and termination of the American Revolution. Interspersed with biographical, political and moral observations. In three volumes. Volume III. Boston: Manning and Loring, 1805. 431-432.