Patriot, Soldier, Lecturer

By Katie Woods, Digital Public Historian

Deborah Sampson Gannett took the ultimate risk by enlisting and serving as a soldier for Massachusetts during the final years of the American Revolutionary War. She remains recognized as one of the country’s first known female soldiers.

Born on December 17, 1760 in Plympton, Massachusetts, Deborah descended from notable early settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, including Myles Standish and William Bradford. Despite this lineage, the Sampson family lived in poverty. Her father, Jonathan Sampson, left when Deborah was five years old, forcing the family to fend for themselves. Unable to care for her eight children, Deborah’s mother, Deborah, made the difficult decision to send her daughter to live with several families. The young Deborah eventually became an indentured servant to the family of Benjamin Thomas in Middleborough.

Although Sampson’s servitude did not allow for a carefree childhood, the Thomas home provided her with some stability. She performed her duties while also learning how to read and write with the Thomas boys’ schoolbooks. When her period of servitude ended in 1778, Sampson earned her living as a school teacher and weaver for the following three years.

During this time, news about the ongoing American Revolutionary War reached the small towns of the Massachusetts countryside. Sampson became drawn to the ideals of American freedom and liberty and decided she wanted to do her part, later recalling:

My mind became agitated with the enquiry–why a nation, separated from us by an ocean more than three thousand miles in extent, should endeavor to enforce on us plans of subjugation…I only seemed to want the license to become one of the severest avengers of the wrong.

It is unclear what exactly prompted Deborah Sampson to disguise herself as a soldier. Around March 1782, she first attempted to enlist in Middleborough as “Timothy Thayer,” but was found out when a neighbor recognized her. In May, Sampson disguised herself once more, successfully enlisting in Bellingham, Massachusetts, under the name of “Robert Shurtleff.” She received a bounty for serving in an Uxbridge company, part of the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. Her company immediately marched from Worcester to West Point, New York, for training.

Sampson’s skills as a soldier stood out, and she received a promotion to the Light Infantry Brigade led by Captain George Webb and commanded by General John Paterson. This elite regiment scouted areas in the neutral zone of the Hudson River Valley, spying on British forces and relaying intelligence. While a part of this infantry, Sampson found herself in several violent clashes. She was wounded several times and even removed a bullet from her own thigh to avoid being discovered.

In 1783, Sampson received a promotion to serve as General Paterson’s aide-de-camp. She was revealed as a woman when she was hospitalized for a fever in Philadelphia over the summer. Despite her disguise, Sampson received no known punishment, instead acquiring an honorable discharge on October 25, 1783, signed by Major General Henry Knox, commander of West Point.

For the years immediately following her discharge, Deborah Sampson led a relatively quiet life. She married Benjamin Gannett, a farmer from Sharon, Massachusetts, on April 7, 1785. They made Sharon their home and had three children — Earl, Mary, and Prudence — and adopted a girl named Susanna Shephard.

In 1792, Sampson Gannett applied to the Massachusetts Legislature for back pay. The Legislature approved her request, resolving:

that the said Deborah exhibited an extraordinary instance of female heroism by discharging the duties of a faithful, gallant soldier, and at the same time preserving the virtue and chastity of her sex unsuspected and unblemished, and was discharged from the service with a fair and honorable character.

She also began petitioning Congress for disability as a veteran, hoping to receive support for the numerous illnesses and health problems acquired from her time in service. She suffered from bouts of poor health for the rest of her life.

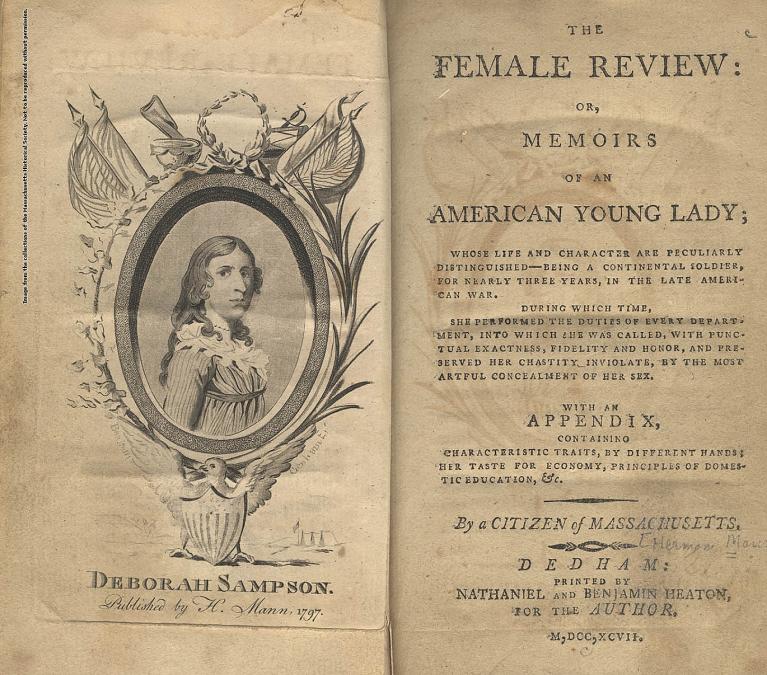

Gannett’s petitions and calls for recognition drew national attention. Massachusetts publisher Herman Mann became fascinated with her story and received permission from Gannett to write her memoir. In 1797, Mann published The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady. This work has since been discredited for significant embellishment.

Still needing to obtain funds for her family, Deborah Sampson Gannett began a lecture tour in 1802. Starting in Boston, Gannett spent close to a year giving lectures in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York – the first American woman to go on a lecture tour. She shared her experiences of the war and often dressed in full military regalia.

Although positively received, this tour did not solve the Gannett family’s financial problems. Sampson Gannett again petitioned Congress. She also received support from notable Revolutionary leaders, such as Paul Revere and General John Paterson, who had become a US Representative (NY). Revere wrote on her behalf to US Representative (MA) William Eustis: “I think her case much more deserving than hundreds to whom Congress have been generous.” Thanks to this support, she was added to the pension roll in 1805 and eventually won a general service pension in 1821. She joined Margaret Corbin, who fought alongside her husband at the Battle of Fort Washington in 1776, as one of the first American women to receive a soldier’s pension.

Gannett died on April 29, 1827 in Sharon, Massachusetts. Four years following her death, her husband petitioned Congress for pay as a soldier’s widower. In 1837, the House Committee on Revolutionary Pensions honored Deborah Sampson, declaring that the American Revolution saw no other “similar example of female heroism, fidelity, and courage” and awarded her husband a spousal pension.

Deborah Sampson Gannett’s legacy as a patriot for the American cause remains vibrant in Massachusetts. In 1982, the Legislature proclaimed her the official state heroine and named May 23 “Deborah Sampson Day.” She also remains a local heroine for the town of Sharon, where the community dedicated a statue of Sampson outside the library in 1989.

Additional Resources

“Biography of Deborah Sampson,” Collection Highlights, Museum of the American Revolution.

“Deborah Sampson (Samson) Gannett Collection.” Sharon Public Library. Accessed May 2025.

Forty, George and Anne Forty. Women War Heroines. London: Arms and Armor Press, 1997.

Freeman, Lucy and Alma Halbert Bond. America’s First Woman Warrior: The Courage of Deborah Sampson. New York: Paragon House, 1992.

Mann, Herman. The Female Review: Life of Deborah Sampson, the Female Soldier in the War of Revolution. New York: William Abbatt, 1916.

Bibliography

Bohrer, Melissa Lukeman. “Soldier with a Secret: Deborah Sampson.” In Glory, Passion, and Principle: The Story of Eight Remarkable Women at the Core of the American Revolution. New York: Atria Books, 2003. 179-213.

Cowan, Alison Leigh. “The Woman Who Sneaked Into George Washington’s Army.” New York Times, July 2, 2019.

Laska, Vera O. "Remember the ladies": Outstanding Women of the American Revolution. Boston: Commonwealth of Massachusetts Bicentennial Commission, 1976.

“Letter from Paul Revere to William Eustis, 20 February, 1804” Miscellaneous Bound Manuscripts, Collections Online, Massachusetts Historical Society. Accessed May 2025.

Michals, Debra. “Deborah Sampson (1760-1827)” National Women’s History Museum. 2015. Last updated January 2023. Accessed May 2025.

Sampson, Deborah. “An Address Delivered in 1802 Various Towns in Massachusets, Rhode Island and New York by Mrs. Deborah Sampson Gannett of Sharon, Massachusetts.” Reprinted by the Sharon Historical Society. Boston: H. M. Hight, 1905.

Sampson, Deborah. Diary of Deborah Sampson Gannett in 1802. Boston: Boston Public Library, 1901.

Sefilippi, Jessie. “Deborah Sampson,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed May 2025.

Young, Alfred F. Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier. New York: Alfred P. Knopf, 2004.